cyber #origen #risk #solution

It's amazing to think about how prevalent issues of cybersecurity and social media have become in our day to day lives. Something that had not even existed a few generations ago is now a legitimate topic in a university class about whether humanity is doomed.

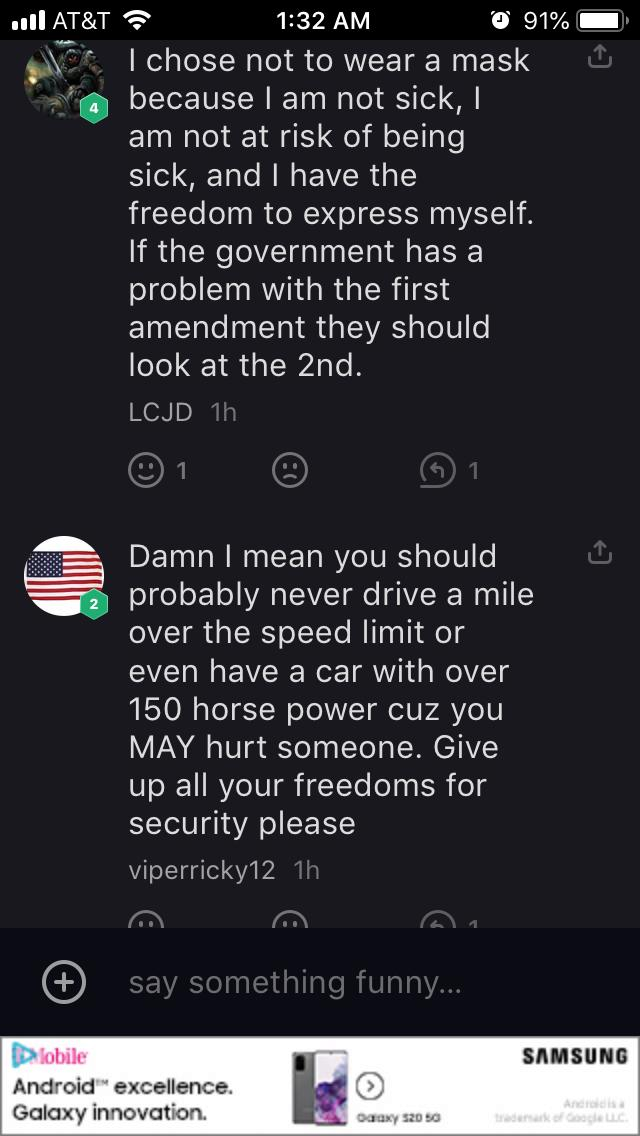

I remember that I genuinely couldn't help but find humor in the day that Donald Trump's twitter being deactivated was BIG news. But after a while it began to make me question the power of those running social media. In a country that is supposed to have free speech, it is very frequent that the words all types of people are censored by those who simply disagree with what is being said. There's a very gray line when it comes to determining whether the censorship of people online is dangerous or beneficial.

Sometimes I find myself thinking that social media may have been one of the worst things ever introduced to mankind, and other days I don't think it's that bad. For a lot of the bad it has done, it's also done a lot of good. But where is the line? When do the cons outweigh the pros? Social media is still a fairly uncharted territory when it comes to the distribution of information. Sometimes when you open an app or webpage, the only thing to protect you from the spread of false information is your own basic sense. I remember there was once a day in elementary school where my class was taught the difference between reliable and unreliable sources on the internet. For some reason this is the one class that has stood out most vividly from my elementary school career. Perhaps the new generations of youth would greatly benefit from more in-depth sessions on how to interpret and use information online, and how to protect themselves against false information, especially considering how much of it now comes from social media. And if people could be taught not to abuse social media, then maybe there wouldn't be a need for online censorship in the future.

Though the world later found out that the Tweet was not posted by Elon himself, it was not out of character for the eclectic billionaire, who is known to be a very large supporter of the adoption and usage of Bitcoin. As a result, Twitter users began to send Bitcoin to an untraceable wallet, hoping their money would double. This was the work of some very talented hackers- who, over the course of the next few minutes, posted similar messages from the official, verified accounts for Apple, Barack Obama, Joe Biden, Mike Bloomberg, Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, and more. In the few seconds before Twitter identified the problem and removed the tweets in question from the platform, hundreds of thousands of dollars in Bitcoin poured into the hackers' wallets.

Though the world later found out that the Tweet was not posted by Elon himself, it was not out of character for the eclectic billionaire, who is known to be a very large supporter of the adoption and usage of Bitcoin. As a result, Twitter users began to send Bitcoin to an untraceable wallet, hoping their money would double. This was the work of some very talented hackers- who, over the course of the next few minutes, posted similar messages from the official, verified accounts for Apple, Barack Obama, Joe Biden, Mike Bloomberg, Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, and more. In the few seconds before Twitter identified the problem and removed the tweets in question from the platform, hundreds of thousands of dollars in Bitcoin poured into the hackers' wallets.

Leave below as comments your memos that grapple with the topic of cyber inspired by the readings, movies & novels (at least one per quarter), your research, experiences, and imagination! Also add a thumbs up to the 5 memos you find most awesome, challenging, and discussion-worthy!

Recall the following instructions: Memos: Every week students will post one memo in response to the readings and associated topic. The memo should be 300–500 words + 1 visual element (e.g., figure, image, hand-drawn picture, art, etc. that complements or is suggestive of your argument). The memo should be tagged with one or more of the following:

origin: How did we get here? Reflection on the historical, technological, political and other origins of this existential crisis that help us better understand and place it in context.

risk: Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the risk associated with this challenge. This risk analysis could be locally in a particular place and time, or globally over a much longer period, in isolation or in relation to other existential challenges (e.g., the environmental devastation that follows nuclear fallout).

policy: What individual and collective actions or policies could be (or have been) undertaken to avert the existential risk associated with this challenge? These could include a brief examination and evaluation of a historical context and policy (e.g., quarantining and plague), a comparison of existing policy options (e.g., cost-benefit analysis, ethical contrast), or design of a novel policy solution.

solutions: Suggestions of what (else) might be done. These could be personal, technical, social, artistic, or anything that might reduce existential risk.

framing: What are competing framings of this existential challenge? Are there any novel framings that could allow us to think about the challenge differently; that would make it more salient? How do different ethical, religious, political and other positions frame this challenge and its consequences (e.g., “End of the Times”).

salience: Why is it hard to think and talk about or ultimately mobilize around this existential challenge? Are there agencies in society with an interest in downplaying the risks associated with this challenge? Are there ideologies that are inconsistent with this risk that make it hard to recognize or feel responsible for?

nuclear/#climate/#bio/#cyber/#emerging: Partial list of topics of focus.

Movie/novel memo: Each week there will be a selection of films and novels. For one session over the course of the quarter, at their discretion, students will post a memo that reflects on a film or fictional rendering of an existential challenge. This should be tagged with:

movie / #novel: How did the film/novel represent the existential challenge? What did this highlight; what did it ignore? How realistic was the risk? How salient (or insignificant) did it make the challenge for you? For others (e.g., from reviews, box office/retail receipts, or contemporary commentary)?