salience

According to last class' poll, I'm not alone in dreading this particular apocalypse. Sure, we might blow ourselves up... but the world is hurtling towards the sort of exponential-heating limits that the Rolling Stone article talks about. CO2 pockets releasing from melting polar caps, existing CO2 emissions continuing to heat the planet... etc.

How can we possibly grapple with that? Nuclear warfare at least relies on action-- we can elect officials who seem unlikely to press the button, pass legislation that makes it harder to press the button, get rid of the bombs connected to the button. And as the professors mentioned in the past class, there have been a number of individuals presented with the opportunity to press that button... and they said no. Not worth it, in their eyes. Death of us all.

Climate change isn't like that. All it needs, at this point, is inaction... and that's all we're doing! All of us! Myself included! Our leaders included, even the leaders that say "hey, I'm going to take action here!" end up passing the most incrementalist changes that extend the lifespan of our ecosystem by about two months. And the actions that need to change are hard, and complicated, and will probably result in a substantial decrease in my current level of luxury. Fruits out of season! Plane trips back home! A partner with a gas-powered car that can take us anywhere we want to go.

There's so much that needs to change, so little time to do it, and so many entrenched ideologies/corporations that are opposed to it. I cannot see how we will get out of this one. Honestly, I would be surprised if we did.

Happy Tuesday!

Sources:

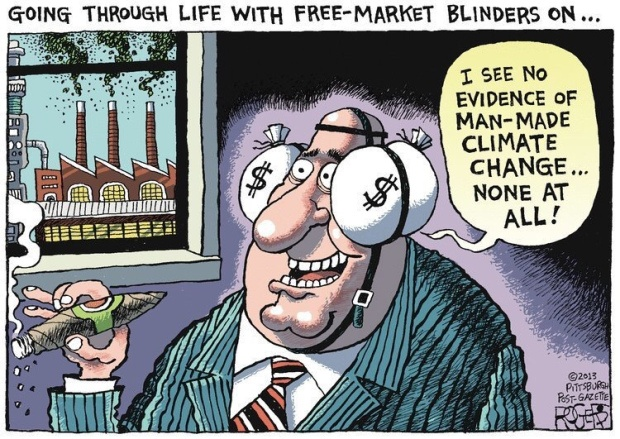

Jeff Darcy, "Climate change denial decimated by hurricanes: Darcy cartoon". (

Sources:

Jeff Darcy, "Climate change denial decimated by hurricanes: Darcy cartoon". (

This collection of charts shows the numerous drastic environmental changes that occurred starting around 1950, the beginning of the Anthropocene.

This collection of charts shows the numerous drastic environmental changes that occurred starting around 1950, the beginning of the Anthropocene.

Leave below as comments your memos that grapple with the topic of climate change, inspired by the readings (Synthesis report from IPCC5, IPCC Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5°C, Bill McKibben's “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math”, Elizabeth Kolbert's “Three scenarios for the future of climate change”; see the syllabus for links), movies & novels (at least one per quarter), your research, experiences, and imagination! Also add a thumbs up to the 5 memos you find most awesome, challenging, and discussion-worthy!

Recall the following instructions: Memos: Every week students will post one memo in response to the readings and associated topic. The memo should be 300–500 words + 1 visual element (e.g., figure, image, hand-drawn picture, art, etc. that complements or is suggestive of your argument). The memo should be tagged with one or more of the following:

origin: How did we get here? Reflection on the historical, technological, political and other origins of this existential crisis that help us better understand and place it in context.

risk: Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the risk associated with this challenge. This risk analysis could be locally in a particular place and time, or globally over a much longer period, in isolation or in relation to other existential challenges (e.g., the environmental devastation that follows nuclear fallout).

policy: What individual and collective actions or policies could be (or have been) undertaken to avert the existential risk associated with this challenge? These could include a brief examination and evaluation of a historical context and policy (e.g., quarantining and plague), a comparison of existing policy options (e.g., cost-benefit analysis, ethical contrast), or design of a novel policy solution.

solutions: Suggestions of what (else) might be done. These could be personal, technical, social, artistic, or anything that might reduce existential risk.

framing: What are competing framings of this existential challenge? Are there any novel framings that could allow us to think about the challenge differently; that would make it more salient? How do different ethical, religious, political and other positions frame this challenge and its consequences (e.g., “End of the Times”).

salience: Why is it hard to think and talk about or ultimately mobilize around this existential challenge? Are there agencies in society with an interest in downplaying the risks associated with this challenge? Are there ideologies that are inconsistent with this risk that make it hard to recognize or feel responsible for?

nuclear/#climate/#bio/#cyber/#emerging: Partial list of topics of focus.

Movie/novel memo: Each week there will be a selection of films and novels. For one session over the course of the quarter, at their discretion, students will post a memo that reflects on a film or fictional rendering of an existential challenge. This should be tagged with:

movie / #novel: How did the film/novel represent the existential challenge? What did this highlight; what did it ignore? How realistic was the risk? How salient (or insignificant) did it make the challenge for you? For others (e.g., from reviews, box office / retail receipts, or contemporary commentary)?