LightService is a powerful and flexible service skeleton framework with an emphasis on simplicity

🔥 It now comes with no external gem dependency. 🔥

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Why LightService?

- Getting started

- Stopping the Series of Actions

- Benchmarking Actions with Around Advice

- Before and After Action Hooks

- Expects and Promises

- Key Aliases

- Logging

- Error Codes

- Action Rollback

- Localizing Messages

- Orchestrating Logic in Organizers

- ContextFactory for Faster Action Testing

- Rails support

- Other implementations

- Contributing

- Release Notes

- License

Why LightService?

What do you think of this code?

class TaxController < ApplicationController

def update

@order = Order.find(params[:id])

tax_ranges = TaxRange.for_region(order.region)

if tax_ranges.nil?

render :action => :edit, :error => "The tax ranges were not found"

return # Avoiding the double render error

end

tax_percentage = tax_ranges.for_total(@order.total)

if tax_percentage.nil?

render :action => :edit, :error => "The tax percentage was not found"

return # Avoiding the double render error

end

@order.tax = (@order.total * (tax_percentage/100)).round(2)

if @order.total_with_tax > 200

@order.provide_free_shipping!

end

redirect_to checkout_shipping_path(@order), :notice => "Tax was calculated successfully"

end

endThis controller violates SRP all over. Also, imagine what it would take to test this beast. You could move the tax_percentage finders and calculations into the tax model, but then you'll make your model logic heavy.

This controller does 3 things in order:

- Looks up the tax percentage based on order total

- Calculates the order tax

- Provides free shipping if the total with tax is greater than $200

The order of these tasks matters: you can't calculate the order tax without the percentage. Wouldn't it be nice to see this instead?

(

LooksUpTaxPercentage,

CalculatesOrderTax,

ProvidesFreeShipping

)This block of code should tell you the "story" of what's going on in this workflow. With the help of LightService you can write code this way. First you need an organizer object that sets up the actions in order and executes them one-by-one. Then you need to create the actions with one method (that will do only one thing).

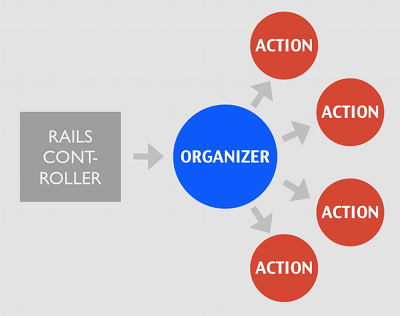

This is how the organizer and actions interact with each other:

class CalculatesTax

extend LightService::Organizer

def self.call(order)

with(:order => order).reduce(

LooksUpTaxPercentageAction,

CalculatesOrderTaxAction,

ProvidesFreeShippingAction

)

end

end

class LooksUpTaxPercentageAction

extend LightService::Action

expects :order

promises :tax_percentage

executed do |context|

tax_ranges = TaxRange.for_region(context.order.region)

context.tax_percentage = 0

next context if object_is_nil?(tax_ranges, context, 'The tax ranges were not found')

context.tax_percentage = tax_ranges.for_total(context.order.total)

next context if object_is_nil?(context.tax_percentage, context, 'The tax percentage was not found')

end

def self.object_is_nil?(object, context, message)

if object.nil?

context.fail!(message)

return true

end

false

end

end

class CalculatesOrderTaxAction

extend ::LightService::Action

expects :order, :tax_percentage

# I am using ctx as an abbreviation for context

executed do |ctx|

order = ctx.order

order.tax = (order.total * (ctx.tax_percentage/100)).round(2)

end

end

class ProvidesFreeShippingAction

extend LightService::Action

expects :order

executed do |ctx|

if ctx.order.total_with_tax > 200

ctx.order.provide_free_shipping!

end

end

endAnd with all that, your controller should be super simple:

class TaxController < ApplicationContoller

def update

@order = Order.find(params[:id])

service_result = CalculatesTax.for_order(@order)

if service_result.failure?

render :action => :edit, :error => service_result.message

else

redirect_to checkout_shipping_path(@order), :notice => "Tax was calculated successfully"

end

end

endI gave a talk at RailsConf 2013 on simple and elegant Rails code where I told the story of how LightService was extracted from the projects I had worked on.

Getting started

Requirements

This gem requires ruby 2.x. Use of generators requires Rails 5+ (tested on Rails 5.x & 6.x only. Will probably work on Rails versions as old as 3.2)

Installation

In your Gemfile:

gem 'light-service'And then

bundle installOr install it yourself as:

gem install light-serviceYour first action

LightService's building blocks are actions that are normally composed within an organizer, but can be run independently. Let's make a simple greeter action. Each action can take an optional list of expected inputs and promised outputs. If these are specified and missing at action start and stop respectively, an exception will be thrown.

class GreetsPerson

extend ::LightService::Action

expects :name

promises :greeting

executed do |context|

context.greeting = "Hey there, #{name}. You enjoying LightService so far?"

end

endWhen an action is run, you have access to its returned context, and the status of the action. You can invoke an

action by calling .execute on its class with key: value arguments, and inspect its status and context like so:

outcome = GreetsPerson.execute(name: "Han")

if outcome.success?

puts outcome.greeting # which was a promised context value

elsif outcome.failure?

puts "Rats... I can't say hello to you"

endYou will notice that actions are set up to promote simplicity, i.e. they either succeed or fail, and they have very clear inputs and outputs. Ideally, they should do exactly one thing. This makes them as easy to test as unit tests.

Your first organizer

LightService provides a facility to compose actions using organizers. This is great when you have a business process to execute that has multiple steps. By composing actions that do exactly one thing, you can sequence simple actions together to perform complex multi-step business processes in a clear manner that is very easy to reason about.

There are advanced ways to sequence actions that can be found later in the README, but we'll keep this simple for now.

First, let's add a second action that we can sequence to run after the GreetsPerson action from above:

class RandomlyAwardsPrize

extend ::LightService::Action

expects :name, :greeting

promises :did_i_win

executed do |context|

prize_num = "#{context.name}__#{context.greeting}".length

prizes = ["jelly beans", "ice cream", "pie"]

did_i_win = rand((1..prize_num)) % 7 == 0

did_i_lose = rand((1..prize_num)) % 13 == 0

if did_i_lose

# When failing, send a message as an argument, readable from the return context

context.fail!("you are exceptionally unlucky")

else

# You can specify 'optional' context items by treating context like a hash.

# Useful for when you may or may not be returning extra data. Ideally, selecting

# a prize should be a separate action that is only run if you win.

context[:prize] = "lifetime supply of #{prizes.sample}" if did_i_win

context.did_i_win = did_i_win

end

end

endAnd here's the organizer that ties the two together. You implement a call class method that takes some arguments and

from there sends them to with in key: value format which forms the initial state of the context. From there, chain

reduce to with and send it a list of action class names in sequence. The organizer will call each action, one

after the other, and build up the context as it goes along.

class WelcomeAPotentiallyLuckyPerson

extend LightService::Organizer

def self.call(name)

with(:name => name).reduce(GreetsPerson, RandomlyAwardsPrize)

end

endWhen an organizer is run, you have access to the context as it passed through all actions, and the overall status

of the organized execution. You can invoke an organizer by calling .call on the class with the expected arguments,

and inspect its status and context just like you would an action:

outcome = WelcomeAPotentiallyLuckyPerson.call("Han")

if outcome.success?

puts outcome.greeting # which was a promised context value

if outcome.did_i_win

puts "And you've won a prize! Lucky you. Please see the front desk for your #{outcome.prize}."

end

else # outcome.failure? is true, and we can pull the failure message out of the context for feedback to the user.

puts "Rats... I can't say hello to you, because #{outcome.message}."

endBecause organizers generally run through complex business logic, and every action has the potential to cause a failure, testing an organizer is functionally equivalent to an integration test.

For further examples, please visit the project's Wiki and review the "Why LightService" section above.

Stopping the Series of Actions

When nothing unexpected happens during the organizer's call, the returned context will be successful. Here is how you can check for this:

class SomeController < ApplicationController

def index

result_context = SomeOrganizer.call(current_user.id)

if result_context.success?

redirect_to foo_path, :notice => "Everything went OK! Thanks!"

else

flash[:error] = result_context.message

render :action => "new"

end

end

endHowever, sometimes not everything will play out as you expect it. An external API call might not be available or some complex business logic will need to stop the processing of the Series of Actions. You have two options to stop the call chain:

- Failing the context

- Skipping the rest of the actions

Failing the Context

When something goes wrong in an action and you want to halt the chain, you need to call fail! on the context object. This will push the context in a failure state (context.failure? # will evalute to true).

The context's fail! method can take an optional message argument, this message might help describing what went wrong.

In case you need to return immediately from the point of failure, you have to do that by calling next context.

In case you want to fail the context and stop the execution of the executed block, use the fail_and_return!('something went wrong') method.

This will immediately leave the block, you don't need to call next context to return from the block.

Here is an example:

class SubmitsOrderAction

extend LightService::Action

expects :order, :mailer

executed do |context|

unless context.order.submit_order_successful?

context.fail_and_return!("Failed to submit the order")

end

# This won't be executed

context.mailer.send_order_notification!

end

end

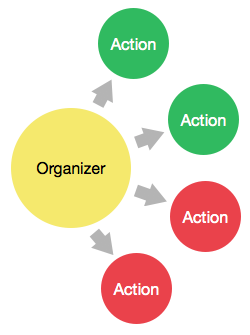

In the example above the organizer called 4 actions. The first 2 actions got executed successfully. The 3rd had a failure, that pushed the context into a failure state and the 4th action was skipped.

Skipping the rest of the actions

You can skip the rest of the actions by calling context.skip_remaining!. This behaves very similarly to the above-mentioned fail! mechanism, except this will not push the context into a failure state.

A good use case for this is executing the first couple of action and based on a check you might not need to execute the rest.

Here is an example of how you do it:

class ChecksOrderStatusAction

extend LightService::Action

expects :order

executed do |context|

if context.order.send_notification?

context.skip_remaining!("Everything is good, no need to execute the rest of the actions")

end

end

end

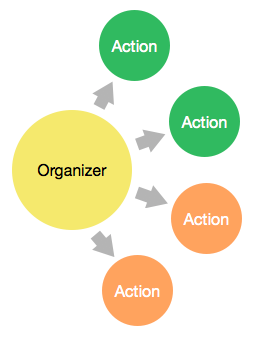

In the example above the organizer called 4 actions. The first 2 actions got executed successfully. The 3rd decided to skip the rest, the 4th action was not invoked. The context was successful.

Benchmarking Actions with Around Advice

Benchmarking your action is needed when you profile the series of actions. You could add benchmarking logic to each and every action, however, that would blur the business logic you have in your actions.

Take advantage of the organizer's around_each method, which wraps the action calls as its reducing them in order.

Check out this example:

class LogDuration

def self.call(context)

start_time = Time.now

result = yield

duration = Time.now - start_time

LightService::Configuration.logger.info(

:action => context.current_action,

:duration => duration

)

result

end

end

class CalculatesTax

extend LightService::Organizer

def self.call(order)

with(:order => order).around_each(LogDuration).reduce(

LooksUpTaxPercentageAction,

CalculatesOrderTaxAction,

ProvidesFreeShippingAction

)

end

endAny object passed into around_each must respond to #call with two arguments: the action name and the context it will execute with. It is also passed a block, where LightService's action execution will be done in, so the result must be returned. While this is a little work, it also gives you before and after state access to the data for any auditing and/or checks you may need to accomplish.

Before and After Action Hooks

In case you need to inject code right before and after the actions are executed, you can use the before_actions and after_actions hooks. It accepts one or multiple lambdas that the Action implementation will invoke. This addition to LightService is a great way to decouple instrumentation from business logic.

Consider this code:

class SomeOrganizer

extend LightService::Organizer

def self.call(ctx)

with(ctx).reduce(actions)

end

def self.actions

[

OneAction,

TwoAction,

ThreeAction

]

end

end

class TwoAction

extend LightService::Action

expects :user, :logger

executed do |ctx|

# Logging information

if ctx.user.role == 'admin'

ctx.logger.info('admin is doing something')

end

ctx.user.do_something

end

endThe logging logic makes TwoAction more complex, there is more code for logging than for business logic.

You have two options to decouple instrumentation from real logic with before_actions and after_actions hooks:

- Declare your hooks in the Organizer

- Attach hooks to the Organizer from the outside

This is how you can declaratively add before and after hooks to the Organizer:

class SomeOrganizer

extend LightService::Organizer

before_actions (lambda do |ctx|

if ctx.current_action == TwoAction

return unless ctx.user.role == 'admin'

ctx.logger.info('admin is doing something')

end

end)

after_actions (lambda do |ctx|

if ctx.current_action == TwoAction

return unless ctx.user.role == 'admin'

ctx.logger.info('admin is DONE doing something')

end

end)

def self.call(ctx)

with(ctx).reduce(actions)

end

def self.actions

[

OneAction,

TwoAction,

ThreeAction

]

end

end

class TwoAction

extend LightService::Action

expects :user

executed do |ctx|

ctx.user.do_something

end

endNote how the action has no logging logic after this change. Also, you can target before and after action logic for specific actions, as the ctx.current_action will have the class name of the currently processed action. In the example above, logging will occur only for TwoAction and not for OneAction or ThreeAction.

Here is how you can declaratively add before_hooks or after_hooks to your Organizer from the outside:

SomeOrganizer.before_actions =

lambda do |ctx|

if ctx.current_action == TwoAction

return unless ctx.user.role == 'admin'

ctx.logger.info('admin is doing something')

end

endThese ideas are originally from Aspect Oriented Programming, read more about them here.

Expects and Promises

The expects and promises macros are rules for the inputs/outputs of an action.

expects describes what keys it needs to execute, and promises makes sure the keys are in the context after the

action is reduced. If either of them are violated, a LightService::ExpectedKeysNotInContextError or

LightService::PromisedKeysNotInContextError exception respectively will be thrown.

This is how it's used:

class FooAction

extend LightService::Action

expects :baz

promises :bar

executed do |context|

context.bar = context.baz + 2

end

endThe expects macro will pull the value with the expected key from the context, and

makes it available to you through a reader.

The promises macro will not only check if the context has the promised keys, it

also sets them for you in the context if you use the accessor with the same name,

much the same way as the expects macro works.

The context object is essentially a smarter-than-normal Hash. Take a look at this spec to see expects and promises used with and without accessors.

Default values for optional Expected keys

When you have an expected key that has a sensible default which should be used everywhere and only overridden on an as-needed basis, you can specify a default value. An example use-case is a flag that allows a failure from a service under most circumstances to avoid failing an entire workflow because of a non-critical action.

LightService provides two mechanisms for specifying default values:

- A static value that is used as-is

- A callable that takes the current context as a param

Using the above use case, consider an action that sends a text message. In most cases,

if there is a problem sending the text message, it might be OK for it to fail. We will

expect an allow_failure key, but set it with a default, like so:

class SendSMS

extend LightService::Action

expects :message, :user

expects :allow_failure, default: true

executed do |context|

sms_api = SMSService.new(key: ENV["SMS_API_KEY"])

status = sms_api.send(ctx.user.mobile_number, ctx.message)

if !status.sent_ok?

ctx.fail!(status.err_msg) unless ctx.allow_failure

end

end

endDefault values can also be processed dynamically by providing a callable. Any values already specified in the context are available to it via Hash key lookup syntax. e.g.

class SendSMS

extend LightService::Action

expects :message, :user

expects :allow_failure, default: ->(ctx) { !ctx[:user].admin? } # Admins must always get SMS'

executed do |context|

sms_api = SMSService.new(key: ENV["SMS_API_KEY"])

status = sms_api.send(ctx.user.mobile_number, ctx.message)

if !status.sent_ok?

ctx.fail!(status.err_msg) unless ctx.allow_failure

end

end

endNote that default values must be specified one at a time on their own line.

You can then call an action or organizer that uses an action with defaults without specifying the expected key that has a default.

Key Aliases

The aliases macro sets up pairs of keys and aliases in an organizer. Actions can access the context using the aliases.

This allows you to put together existing actions from different sources and have them work together without having to modify their code. Aliases will work with or without action expects.

Say for example you have actions AnAction and AnotherAction that you've used in previous projects. AnAction provides :my_key but AnotherAction needs to use that value but expects :key_alias. You can use them together in an organizer like so:

class AnOrganizer

extend LightService::Organizer

aliases :my_key => :key_alias

def self.call(order)

with(:order => order).reduce(

AnAction,

AnotherAction,

)

end

end

class AnAction

extend LightService::Action

promises :my_key

executed do |context|

context.my_key = "value"

end

end

class AnotherAction

extend LightService::Action

expects :key_alias

executed do |context|

context.key_alias # => "value"

end

endLogging

Enable LightService's logging to better understand what goes on within the series of actions, what's in the context or when an action fails.

Logging in LightService is turned off by default. However, turning it on is simple. Add this line to your project's config file:

LightService::Configuration.logger = Logger.new(STDOUT)You can turn off the logger by setting it to nil or /dev/null.

LightService::Configuration.logger = Logger.new('/dev/null')Watch the console while you are executing the workflow through the organizer. You should see something like this:

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - calling organizer <TestDoubles::MakesTeaAndCappuccino>

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - keys in context: :tea, :milk, :coffee

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - executing <TestDoubles::MakesTeaWithMilkAction>

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - expects: :tea, :milk

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - promises: :milk_tea

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - keys in context: :tea, :milk, :coffee, :milk_tea

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - executing <TestDoubles::MakesLatteAction>

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - expects: :coffee, :milk

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - promises: :latte

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - keys in context: :tea, :milk, :coffee, :milk_tea, :latteThe log provides a blueprint of the series of actions. You can see what organizer is invoked, what actions are called in what order, what do the expect and promise and most importantly what keys you have in the context after each action is executed.

The logger logs its messages with "INFO" level. The exception to this is the event when an action fails the context. That message is logged with "WARN" level:

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - calling organizer <TestDoubles::MakesCappuccinoAddsTwoAndFails>

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - keys in context: :milk, :coffee

W, [DATE] WARN -- : [LightService] - :-((( <TestDoubles::MakesLatteAction> has failed...

W, [DATE] WARN -- : [LightService] - context message: Can't make a latte from a milk that's too hot!The log message will show you what message was added to the context when the action pushed the context into a failure state.

The event of skipping the rest of the actions is also captured by its logs:

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - calling organizer <TestDoubles::MakesCappuccinoSkipsAddsTwo>

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - keys in context: :milk, :coffee

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - ;-) <TestDoubles::MakesLatteAction> has decided to skip the rest of the actions

I, [DATE] INFO -- : [LightService] - context message: Can't make a latte with a fatty milk like that!You can specify the logger on the organizer level, so the organizer does not use the global logger.

class FooOrganizer

extend LightService::Organizer

log_with Logger.new("/my/special.log")

endError Codes

You can add some more structure to your error handling by taking advantage of error codes in the context. Normally, when something goes wrong in your actions, you fail the process by setting the context to failure:

class FooAction

extend LightService::Action

executed do |context|

context.fail!("I don't like what happened here.")

end

endHowever, you might need to handle the errors coming from your action pipeline differently. Using an error code can help you check what type of expected error occurred in the organizer or in the actions.

class FooAction

extend LightService::Action

executed do |context|

unless (service_call.success?)

context.fail!("Service call failed", error_code: 1001)

end

# Do something else

unless (entity.save)

context.fail!("Saving the entity failed", error_code: 2001)

end

end

endAction Rollback

Sometimes your action has to undo what it did when an error occurs. Think about a chain of actions where you need

to persist records in your data store in one action and you have to call an external service in the next. What happens if there

is an error when you call the external service? You want to remove the records you previously saved. You can do it now with

the rolled_back macro.

class SaveEntities

extend LightService::Action

expects :user

executed do |context|

context.user.save!

end

rolled_back do |context|

context.user.destroy

end

endYou need to call the fail_with_rollback! method to initiate a rollback for actions starting with the action where the failure

was triggered.

class CallExternalApi

extend LightService::Action

executed do |context|

api_call_result = SomeAPI.save_user(context.user)

context.fail_with_rollback!("Error when calling external API") if api_call_result.failure?

end

endUsing the rolled_back macro is optional for the actions in the chain. You shouldn't care about undoing non-persisted changes.

The actions are rolled back in reversed order from the point of failure starting with the action that triggered it.

See this acceptance test to learn more about this functionality.

You may find yourself directly using an action that can roll back by calling .execute instead of using it from within an Organizer.

If this action fails and attempts a rollback, a FailWithRollbackError exception will be raised. This is so that the organizer can

rollback the actions one by one. If you don't want to wrap your call to the action with a begin, rescue FailWithRollbackError

block, you can introspect the context like so, and keep your usage of the action clean:

class FooAction

extend LightService::Action

executed do |context|

# context.organized_by will be nil if run from an action,

# or will be the class name if run from an organizer

if context.organized_by.nil?

context.fail!

else

context.fail_with_rollback!

end

end

endLocalizing Messages

Built-in localization adapter

The built-in adapter simply uses a manually created dictionary to search for translations.

# lib/light_service_translations.rb

LightService::LocalizationMap.instance[:en] = {

:foo_action => {

:light_service => {

:failures => {

:exceeded_api_limit => "API limit for service Foo reached. Please try again later."

},

:successes => {

:yay => "Yaaay!"

}

}

}

}class FooAction

extend LightService::Action

executed do |context|

unless service_call.success?

context.fail!(:exceeded_api_limit)

# The failure message used here equates to:

# LightService::LocalizationMap.instance[:en][:foo_action][:light_service][:failures][:exceeded_api_limit]

end

end

endNested classes will work too: App::FooAction, for example, would be translated to app/foo_action hash key.

:en is the default locale, but you can switch it whenever you want with

LightService::Configuration.locale = :itIf you have I18n loaded in your project the default adapter will automatically be updated to use it.

But would you want to opt for the built-in localization adapter you can force it with

LightService::Configuration.localization_adapter = LightService::LocalizationAdapterI18n localization adapter

If I18n is loaded into your project, LightService will automatically provide a mechanism for easily translating your error or success messages via I18n.

class FooAction

extend LightService::Action

executed do |context|

unless service_call.success?

context.fail!(:exceeded_api_limit)

# The failure message used here equates to:

# I18n.t(:exceeded_api_limit, scope: "foo_action.light_service.failures")

end

end

endThis also works with nested classes via the ActiveSupport #underscore method, just as ActiveRecord performs localization lookups on models placed inside a module.

module PaymentGateway

class CaptureFunds

extend LightService::Action

executed do |context|

if api_service.failed?

context.fail!(:funds_not_available)

end

# this failure message equates to:

# I18n.t(:funds_not_available, scope: "payment_gateway/capture_funds.light_service.failures")

end

end

endIf you need to provide custom variables for interpolation during localization, pass that along in a hash.

module PaymentGateway

class CaptureFunds

extend LightService::Action

executed do |context|

if api_service.failed?

context.fail!(:funds_not_available, last_four: "1234")

end

# this failure message equates to:

# I18n.t(:funds_not_available, last_four: "1234", scope: "payment_gateway/capture_funds.light_service.failures")

# the translation string itself being:

# => "Unable to process your payment for account ending in %{last_four}"

end

end

endCustom localization adapter

You can also provide your own custom localization adapter if your application's logic is more complex than what is shown here.

To provide your own custom adapter, use the configuration setting and subclass the default adapter LightService provides.

LightService::Configuration.localization_adapter = MyLocalizer.new

# lib/my_localizer.rb

class MyLocalizer < LightService::I18n::LocalizationAdapter

# I just want to change the default lookup path

# => "light_service.failures.payment_gateway/capture_funds"

def i18n_scope_from_class(action_class, type)

"light_service.#{type.pluralize}.#{action_class.name.underscore}"

end

endTo get the value of a fail! or succeed! message, simply call #message on the returned context.

Orchestrating Logic in Organizers

The Organizer - Action combination works really well for simple use cases. However, as business logic gets more complex, or when LightService is used in an ETL workflow, the code that routes the different organizers becomes very complex and imperative.

In the past, this was solved using Orchestrators. As of Version 0.9.0 Orchestrators have been deprecated. All their functionality is now usable directly within Organizers. Read on to understand how to orchestrate workflows from within a single Organizer.

Let's look at a piece of code that does basic data transformations:

class ExtractsTransformsLoadsData

def self.run(connection)

context = RetrievesConnectionInfo.call(connection)

context = PullsDataFromRemoteApi.call(context)

retrieved_items = context.retrieved_items

if retrieved_items.empty?

NotifiesEngineeringTeamAction.execute(context)

end

retrieved_items.each do |item|

context[:item] = item

TransformsData.call(context)

end

context = LoadsData.call(context)

SendsNotifications.call(context)

end

endThe LightService::Context is initialized with the first action, that context is passed around among organizers and actions. This code is still simpler than many out there, but it feels very imperative: it has conditionals, iterators in it. Let's see how we could make it a bit more simpler with a declarative style:

class ExtractsTransformsLoadsData

extend LightService::Organizer

def self.call(connection)

with(:connection => connection).reduce(actions)

end

def self.actions

[

RetrievesConnectionInfo,

PullsDataFromRemoteApi,

reduce_if(->(ctx) { ctx.retrieved_items.empty? }, [

NotifiesEngineeringTeamAction

]),

iterate(:retrieved_items, [

TransformsData

]),

LoadsData,

SendsNotifications

]

end

endThis code is much easier to reason about, it's less noisy and it captures the goal of LightService well: simple, declarative code that's easy to understand.

The 9 different orchestrator constructs an organizer can have:

reduce_untilreduce_ifreduce_if_elsereduce_caseiterateexecutewith_callbackadd_to_contextadd_aliases

reduce_until behaves like a while loop in imperative languages, it iterates until the provided predicate in the lambda evaluates to true. Take a look at this acceptance test to see how it's used.

reduce_if will reduce the included organizers and/or actions if the predicate in the lambda evaluates to true. This acceptance test describes this functionality.

reduce_if_else takes three arguments, a condition lambda, a first set of "if true" steps, and a second set of "if false" steps. If the lambda evaluates to true, the "if true" steps are executed, otherwise the "else steps" are executed. This acceptance test describes this functionality.

reduce_case behaves like a Ruby case statement. The first parameter value is the key of the value within the context that will be worked with. The second parameter when is a hash where the keys are conditional values and the values are steps to take if the condition matches. The final parameter else is a set of steps to take if no conditions within the when parameter are met. This acceptance test describes this functionality.

iterate gives your iteration logic, the symbol you define there has to be in the context as a key. For example, to iterate over items you will use iterate(:items) in your steps, the context needs to have items as a key, otherwise it will fail. The organizer will singularize the collection name and will put the actual item into the context under that name. Remaining with the example above, each element will be accessible by the name item for the actions in the iterate steps. This acceptance test should provide you with an example.

To take advantage of another organizer or action, you might need to tweak the context a bit. Let's say you have a hash, and you need to iterate over its values in a series of action. To alter the context and have the values assigned into a variable, you need to create a new action with 1 line of code in it. That seems a lot of ceremony for a simple change. You can do that in a execute method like this execute(->(ctx) { ctx[:some_values] = ctx.some_hash.values }). This test describes how you can use it.

Use with_callback when you want to execute actions with a deferred and controlled callback. It works similar to a Sax parser, I've used it for processing large files. The advantage of it is not having to keep large amount of data in memory. See this acceptance test as a working example.

add_to_context can add key-value pairs on the fly to the context. This functionality is useful when you need a value injected into the context under a specific key right before the subsequent actions are executed. Keys are also made available as accessors on the context object and can be used just like methods exposed via expects and promises. This test describes its functionality.

Your action needs a certain key in the context but it's under a different one? Use the function add_aliases to alias an existing key in the context under the desired key. Take a look at this test to see an example.

ContextFactory for Faster Action Testing

As the complexity of your workflow increases, you will find yourself spending more and more time creating a context (LightService::Context it is) for your action tests. Some of this code can be reused by clever factories, but still, you are using a context that is artificial, and can be different from what the previous actions produced. This is especially true, when you use LightService in ETLs, where you start out with initial data and your actions are mutating its state.

Here is an example:

class SomeOrganizer

extend LightService::Organizer

def self.call(ctx)

with(ctx).reduce(actions)

end

def self.actions

[

ETL::ParsesPayloadAction,

ETL::BuildsEnititiesAction,

ETL::SetsUpMappingsAction,

ETL::SavesEntitiesAction,

ETL::SendsNotificationAction

]

end

endYou should test your workflow from the outside, invoking the organizer’s call method and verify that the data was properly created or updated in your data store. However, sometimes you need to zoom into one action, and setting up the context to test it is tedious work. This is where ContextFactory can be helpful.

In order to test the third action ETL::SetsUpMappingAction, you have to have several entities in the context. Depending on the logic you need to write code for, this could be a lot of work. However, by using the ContextFactory in your spec, you could easily have a prepared context that’s ready for testing:

require 'spec_helper'

require 'light-service/testing'

RSpec.describe ETL::SetsUpMappingsAction do

let(:context) do

LightService::Testing::ContextFactory

.make_from(SomeOrganizer)

.for(described_class)

.with(:payload => File.read(‘spec/data/payload.json’)

end

it ‘works like it should’ do

result = described_class.execute(context)

expect(result).to be_success

end

endThis context then can be passed to the action under test, freeing you up from the 20 lines of factory or fixture calls to create a context for your specs.

In case your organizer has more logic in its call method, you could create your own test organizer in your specs like you can see it in this acceptance test. This is reusable in all your action tests.

Rails support

LightService includes Rails generators for creating both Organizers and Actions along with corresponding tests. Currently only RSpec is supported (PR's for supporting MiniTest are welcome)

Note: Generators are namespaced to light_service not light-service due to Rake name constraints.

Organizer generation

rails generate light_service:organizer My::SuperFancy::Organizer

# -- or

rails generate light_service:organizer my/super_fancy/organizerOptions for this generator are:

--dir=<SOME_DIR>.<SOME_DIR>defaults toorganizers. Will write organizers to/app/organizers, and specs to/spec/organizers--no-tests. Default is--tests. Will generate a test file matching the namespace you've supplied.

Action generation

rails generate light_service:action My::SuperFancy::Action

# -- or

rails generate light_service:action my/super_fancy/actionOptions for this generator are:

--dir=<SOME_DIR>.<SOME_DIR>defaults toactions. Will write actions to/app/actions, and specs to/spec/actions--no-tests. Defaults is--tests. Will generate a test file matching the namespace you've supplied.--no-roll-back. Default is--roll-back. Will generate arolled_backblock for you to implement with roll back functionality.

Advanced action generation

You are able to optionally specify expects and/or promises keys during generation

rails generate light_service:action CrankWidget expects:one_fish,two_fish promises:red_fish,blue_fishWhen specifying expects, convenience variables will be initialized in the executed block so that you don't have to call

them through the context. A stub context will be created in the test file using these keys too.

When specifying promises, specs will be created testing for their existence after executing the action.

Other implementations

| Language | Repo | Author |

|---|---|---|

| Python | pyservice | @adomokos |

| PHP | light-service | @douglasgreyling |

| JavaScript | light-service.js | @douglasgreyling |

Contributing

- Fork it

- Create your feature branch (

git checkout -b my-new-feature) - Commit your changes (

git commit -am 'Added some feature') - Push to the branch (

git push origin my-new-feature) - Create new Pull Request

Huge thanks to the contributors!

Release Notes

Follow the release notes in this document.

License

LightService is released under the MIT License.