Important Notice:

This site and algorithm is ${\textsf{\color{red}for research users only, not commercial use.}}$ Commercial users should contact exclusive DunedinPACE licensee TruDiagnosticTM.

News

DunedinPACE now works on EPICv2!

Follow instructions and formatting as for EPICv1 or 450k (below). The function will detect EPICv2 data (if replicate suffixes are retained in the rownames) and will lower the proportionOfProbesRequired = 0.8 to 0.7 as EPICv2 is already missing some probes that were originally in 450k and EPICv1. More evidence supporting DunedinPACE in EPICv2 can be in Karen Sugden's excellent report.

DunedinPACE website is online

A new website with information on DunedinPACE, hosted by Avshalom Caspi and Terrie Moffitt's lab is is now live. There you can find additional information about DunedinPACE, cohorts and studies where it has been deployed, some of the key findings, and interesting advancements and news related to the DunedinPACE tool.

Introduction to DunedinPACE

DunedinPACE is a first of its kind blood DNA methylation biomarker of the pace of biological aging. It is designed to function as a speedometer for the aging process, estimating tehir pace of aging from a single blood sample. DunedinPACE values quantify how much faster or slower an individual is aging relative to the normative rate of one year of aging per year of calendar time.

How was DunedinPACE developed?

DunedinPACE was developed to predict a Pace of Aging phenotype in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study. The version of the Pace of Aging used to train DunedinPACE was a composite of rates of change in 19 biomarkers of organ system integrity measured over four time points spanning 20 years of follow-up as the cohort aged from 26 to 45.

What is the evidence for using DunedinPACE to measure aging?

There are three lines of evidence that support the validity of DunedinPACE: First, DunedinPACE is predictive of diverse aging related outcomes, including disease, disability, and mortality[^1],[^2],[^3],[^4],[^5]. Second, DunedinPACE is associated with social determinants of healthy aging in young, midlife, and older adults[^1],[^6],[^7],[^8],[^9],[^10]. Third, Dunedin PACE shows evidence of being modified by calorie restriction[^11], an intervention that modifies the basic biology of aging in animal experiments[^12].

What do I need to run DunedinPACE?

To run the package, you need DNA methylation data produced by the Illumina 450k, EPIC, or EPIC V2 arrays. The data should consist of a matrix of beta values (percent methylation at the CpG site) and must be formatted as follows: rows are individual probes; columns are samples; rownames are Illumina CpG probe names (i.e. cg###########). Although DunedinPACE reflects 'pace of aging', it is computed from a single measure DNA methylation data.

Once you have downloaded and installed the package, you simply load DunedinPACE library, load the beta matrix of your date into R and run the PACEProjector() function on the matrix. The output will be a vector of DunedinPACE values matched to sample IDs.

The easiest way to implement DunedinPACE is load the full beta matrix with all available CpGs (i.e. the whole genome). However, if you wish to work with a smaller data object, you can select the needed CpG sites from your data using the function getrequired probes() with the backgroundList argument set to “TRUE” (backgroundList = TRUE). This will return a matrix of 20,000 probes, including the DunedinPACE probes and a set of probes used for background normalization that ensure the computed values can be compared to the reference value of 1 year of biological aging per calendar year. (The default setting is backgroundList = FALSE, but will return only the 173 probes used to calculate DunedinPACE, but not the probes required for normalization).

What values should I expect the package to return?

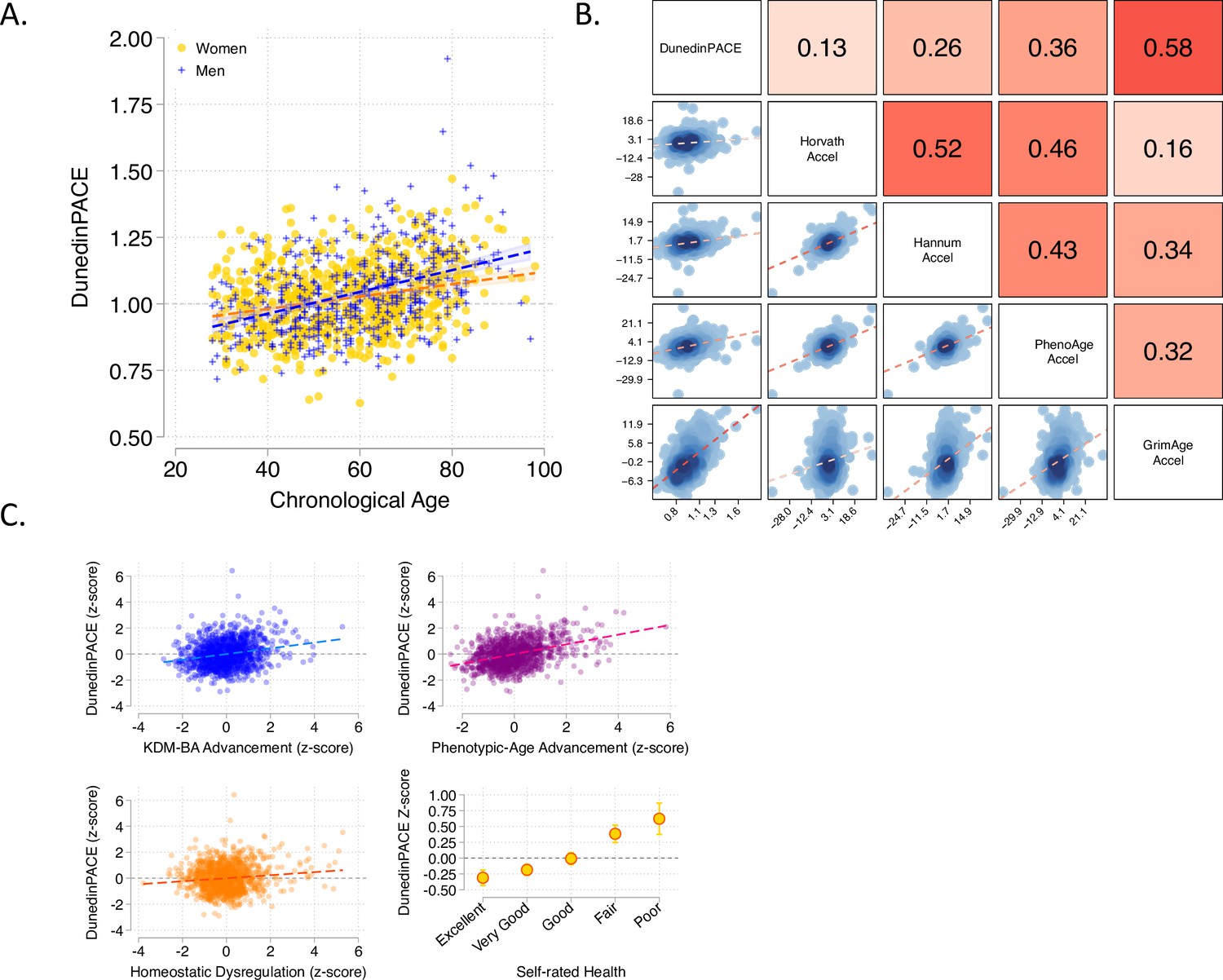

A “normal” DunedinPACE value for a midlife adult is 1.0. Younger people tend to have somewhat slower DunedinPACE values and older people tend to have somewhat faster DunedinPACE values (see Panel A from Figure below):

).

).

Citation for the original paper introducing DunedinPACE in more detail:

Belsky DW, Caspi A, Corcoran DL, Sugden K, Poulton R, Arseneault L, Baccarelli A, Chamarti K, Gao X, Hannon E, et al. 2022. DunedinPACE, a DNA methylation biomarker of the pace of aging. Deelen J, editor. eLife. 11:e73420. doi:10.7554/eLife.73420.

The DunedinPACE R package

The DunedinPACE R package allows users to calculate DunedinPACE in their own DNA methylation dataset. Given a set of methylation beta values, where rows are probes and columns are subjects, this tool will produce DunedinPACE. All columns should correspond to Rownames should correspond to Illumina CpG probe names.

Installation (via devtools):

To install the DunedinPACE and associated vignette, please use the following code:

devtools::install_github("danbelsky/DunedinPACE", build_vignettes = TRUE)To view the associated vignette, load the DunedinPACE package and use the following:

library(DunedinPACE)

vignette("DunedinPACE")PACEProjector()

Usage:

The primary function in the DundedinPACE package is the PACEProjector() function. The PACEProjector() function calculates DunedinPACE for the provided dataset.

We recommend loading a beta matrix containing all available CpGs, but options for working with a subset of the full 450k or EPIC array datasets are provided below.

# load the DunedinPACE package

library("DunedinPACE")

# Apply function to matrix of beta values (here called 'betas').

PACEProjector(betas)Input:

betas:

Matrix or data.frame of beta values where rownames are probe ids and column names should correspond to sample names.

Ensure beta values are numeric and that missing values should be coded as 'NA'proportionOfProbesRequired:

This is the proportion of probes required to have a non-missing value for both the sample to have

DunedinPACE calculated, as well as to determine if we can impute the mean from the current cohort.

By default, this is set to 0.7Output:

A vector of DunedinPACE estimates.

getRequiredProbes()

Usage:

To see the CpG probes required by the DunedinPACE package.

getRequiredProbes()Input:

No input required.

Output

getRequiredProbes(backgroundList = FALSE) returns 173 probes used for calculating DunedinPACE directly.

getRequiredProbes(backgroundList = TRUE) returns 173 probes used for calculating DunedinPACE directly, as well as 19827 probes used in the normalization process.

We do not recommend excluding the 19827 probes used for normalization and calculating DunedinPACE using only the 173 DunedinPACE associated probes, as this will affect DunedinPACE estimates.

Key References

[^1]: Belsky, D.W., Caspi, A., Corcoran, D.L., Sugden, K., Poulton, R., Arseneault, L., Baccarelli, A., Chamarti, K., Gao, X., and Hannon, E. (2022). DunedinPACE, a DNA methylation biomarker of the pace of aging. Elife 11, e73420. [^2]: Faul, J.D., Kim, J.K., Levine, M.E., Thyagarajan, B., Weir, D.R., and Crimmins, E.M. (2023). Epigenetic-based age acceleration in a representative sample of older Americans: Associations with aging-related morbidity and mortality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120, e2215840120. [^3]: Föhr, T., Waller, K., Viljanen, A., Rantanen, T., Kaprio, J., Ollikainen, M., and Sillanpää, E. (2023). Mortality associations with DNA methylation-based biological aging and physical functioning measures across a 20-year follow-up period. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, glad026. [^4]: Kresovich, J.K., Sandler, D.P., and Taylor, J.A. (2023). Methylation-Based Biological Age and Hypertension Prevalence and Incidence. Hypertension 80, 1213–1222. [^5]: Lin, W.-Y. (2023). Epigenetic clocks derived from western samples differentially reflect Taiwanese health outcomes. Front Genet 14, 1089819. 10.3389/fgene.2023.1089819. [^6]: Sugden, K., Moffitt, T.E., Arpawong, T.E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D.W., Corcoran, D.L., Crimmins, E.M., Hannon, E., Houts, R., Mill, J.S., et al. (2023). Cross-National and Cross-Generational Evidence That Educational Attainment May Slow the Pace of Aging in European-Descent Individuals. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, gbad056. 10.1093/geronb/gbad056. [^7]: Kim, K., Yaffe, K., Rehkopf, D.H., Zheng, Y., Nannini, D.R., Perak, A.M., Nagata, J.M., Miller, G.E., Zhang, K., and Lloyd-Jones, D.M. (2023). Association of adverse childhood experiences with accelerated epigenetic aging in midlife. JAMA network open 6, e2317987–e2317987. [^8]: Shen, B., Mode, N.A., Hooten, N.N., Pacheco, N.L., Ezike, N., Zonderman, A.B., and Evans, M.K. (2023). Association of Race and Poverty Status With DNA Methylation–Based Age. JAMA Network Open 6, e236340–e236340. [^9]: Andrasfay, T., and Crimmins, E. (2023). Occupational characteristics and epigenetic aging among older adults in the United States. Epigenetics 18, 2218763. [^10]: Raffington, L., Schwaba, T., Aikins, M., Richter, D., Wagner, G.G., Harden, K.P., Belsky, D.W., and Tucker-Drob, E.M. (2023). Associations of socioeconomic disparities with buccal DNA-methylation measures of biological aging. Clinical Epigenetics 15, 70. [^11]: Waziry, R., Ryan, C.P., Corcoran, D.L., Huffman, K.M., Kobor, M.S., Kothari, M., Graf, G.H., Kraus, V.B., Kraus, W.E., and Lin, D.T.S. (2023). Effect of long-term caloric restriction on DNA methylation measures of biological aging in healthy adults from the CALERIE trial. Nature Aging, 1–10. [^12]: Le Couteur, D.G., Raubenheimer, D., Solon-Biet, S., de Cabo, R., and Simpson, S.J. (2022). Does diet influence aging? Evidence from animal studies. J Intern Med. 10.1111/joim.13530.