The Document

- The Gist

Shortlink:

http://bit.ly/dbfollow

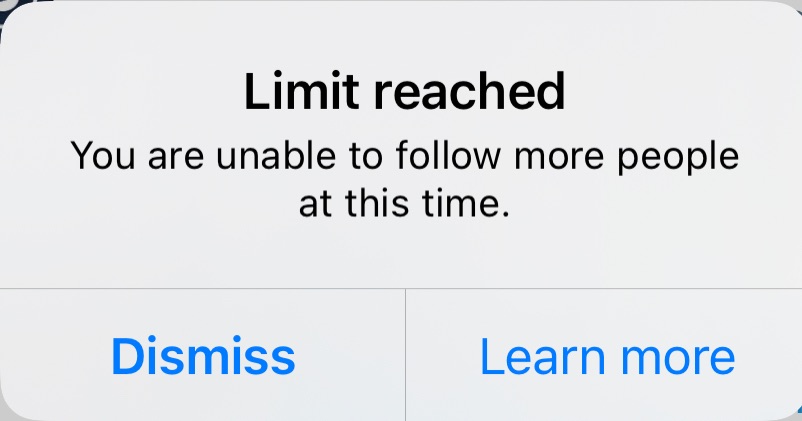

There is a limit to how many accounts you can follow on Twitter. It was finally documented in this official help document, dated March 2019, but for more than ten years, it was implemented without any explanation from the service, and was known only to those of us who'd actually encountered it.

Here's what happens when I try to follow a new account from @NeoYokel:

I was only able to verify that this has been the case since October 20th, 2017 - naturally, I didn't bother to note the actual date I first received that notice.

If you're a recent follower of mine and you've found this document, please know that I have seen your expressed desire to keep in touch in some way (which is what following someone "says," I think we can agree,) and have probably responded by adding you to one of my Twitter Lists. You may have received a notification about this, but if you haven't, it's because I have not yet chosen to make the List to which I added you public.

I also want you to know that I am available to speak directly about this if you have questions - whether that be on Twitter, by email, or otherwise. Here's my personal phone number: +1 (573) 823-4380

For whatever it's worth, thanks for the follow. I hope to hear from you but if I don't, thanks okay, too.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69487311/GettyImages_840299164.0.jpg) Getty Images/iStockphoto

Getty Images/iStockphoto:no_upscale\(\)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22684386/Gatekeepers_Art2_1920x1080.jpg) Adam Hayes for Vox

Adam Hayes for Vox

Fleets (Twitter)

Fleets (Twitter)

Photo by Kevin Erdvig, treatment by Nathan Baschez

Photo by Kevin Erdvig, treatment by Nathan Baschez

108 is going to be an important place to start.

Twitter is the only context where I do not currently see a need for increased emphasis on self-curation at this time considering how that all appearances have indicated that Twitter is algorithmically minimizing my content for specific reasons - I would argue that they were once the same reasons Twitter encouraged.