Turbo Vision

A modern port of Turbo Vision 2.0, the classical framework for text-based user interfaces. Now cross-platform and with Unicode support.

I started this as a personal project at the very end of 2018. By May 2020 I considered it was very close to feature parity with the original, and decided to make it open.

The original goals of this project were:

- Making Turbo Vision work on Linux by altering the legacy codebase as little as possible.

- Keeping it functional on DOS/Windows.

- Being as compatible as possible at the source code level with old Turbo Vision applications. This led me to implement some of the Borland C++ RTL functions, as explained below.

At one point I considered I had done enough, and that any attempts at revamping the library and overcoming its original limitations would require either extending the API or breaking backward compatibility, and that a major rewrite would be most likely necessary.

However, between July and August 2020 I found the way to integrate full-fledged Unicode support into the existing architecture, wrote the Turbo text editor and also made the new features available on Windows. So I am confident that Turbo Vision can now meet many of the expectations of modern users and programmers.

The original location of this project is https://github.com/magiblot/tvision.

Table of contents

- What is Turbo Vision good for?

- How do I use Turbo Vision?

- Releases and downloads

- Build environment

- Features

- API changes

- Applications using Turbo Vision

- Unicode support

- Clipboard interaction

- Extended color support

What is Turbo Vision good for?

A lot has changed since Borland created Turbo Vision in the early 90's. Many GUI tools today separate appearance specification from behaviour specification, use safer or dynamic languages which do not segfault on error, and support either parallel or asynchronous programming, or both.

Turbo Vision does not excel at any of those, but it certainly overcomes many of the issues programmers still face today when writing terminal applications:

-

Forget about terminal capabilities and direct terminal I/O. When writing a Turbo Vision application, all you have to care about is what you want your application to behave and look like—there is no need to add workarounds in your code. Turbo Vision tries its best to produce the same results on all environments. For example: in order to get a bright background color on the Linux console, the blink attribute has to be set. Turbo Vision does this for you.

-

Reuse what has already been done. Turbo Vision provides many widget classes (also known as views), including resizable, overlapping windows, pull-down menus, dialog boxes, buttons, scroll bars, input boxes, check boxes and radio buttons. You may use and extend these; but even if you prefer creating your own, Turbo Vision already handles event dispatching, display of fullwidth Unicode characters, etc.: you do not need to waste time rewriting any of that.

-

Can you imagine writing a text-based interface that works both on Linux and Windows (and thus is cross-platform) out-of-the-box, with no

#ifdefs? Turbo Vision makes this possible. First: Turbo Vision keeps on usingchararrays instead of relying on the implementation-defined and platform-dependentwchar_torTCHAR. Second: thanks to UTF-8 support insetlocalein recent versions of Microsoft's RTL, code like the following will work as intended:std::ifstream f("コンピュータ.txt"); // On Windows, the RTL converts this to the system encoding on-the-fly.

How do I use Turbo Vision?

You can get started with the Turbo Vision For C++ User's Guide, and look at the sample applications hello, tvdemo and tvedit. Once you grasp the basics,

I suggest you take a look at the Turbo Vision 2.0 Programming Guide, which is, in my opinion, more intuitive and easier to understand, despite using Pascal. By then you will probably be interested in the palette example, which contains a detailed description of how palettes are used.

Don't forget to check out the features and API changes sections as well.

Releases and downloads

This project has no stable releases for the time being. If you are a developer, try to stick to the latest commit and report any issues you find while upgrading.

If you just want to test the demo applications:

- Unix systems: you'll have to build Turbo Vision yourself. You may follow the build instructions below.

- Windows: you can find up-to-date binaries in the Actions section. Click on the first successful workflow (with a green tick) in the list. At the bottom of the workflow page, as long as you have logged in to GitHub, you'll find an Artifacts section with the following files:

examples-dos32.zip: 32-bit executables built with Borland C++. No Unicode support.examples-x86.zip: 32-bit executables built with MSVC. Windows Vista or later required.examples-x64.zip: 64-bit executables built with MSVC. x64 Windows Vista or later required.

Build environment

Linux

Turbo Vision can be built as an static library with CMake and GCC/Clang.

cmake . -B ./build -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release && # Could also be 'Debug', 'MinSizeRel' or 'RelWithDebInfo'.

cmake --build ./build # or `cd ./build; make`CMake versions older than 3.13 may not support the -B option. You can try the following instead:

mkdir -p build; cd build

cmake .. -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release &&

cmake --build .The above produces the following files:

libtvision.a, which is the Turbo Vision library.- The demo applications

hello,tvdemo,tvedit,tvdir, which were bundled with the original Turbo Vision (although some of them have a few improvements). - The demo applications

mmenuandpalettefrom Borland's Technical Support. tvhc, the Turbo Vision Help Compiler.

The library and executables can be found in ./build.

The build requirements are:

- A compiler supporting C++14.

libncursesw(note the 'w').libgpmfor mouse support on the Linux console (optional).

If your distribution provides separate devel packages (e.g. libncurses-dev, libgpm-dev in Debian-based distros), install these too.

The runtime requirements are:

xselorxclipfor clipboard support in X11 environments.wl-clipboardfor clipboard support in Wayland environments.

The minimal command line required to build a Turbo Vision application (e.g. hello.cpp with GCC) from this project's root is:

g++ -std=c++14 -o hello hello.cpp ./build/libtvision.a -Iinclude -lncursesw -lgpmYou may also need:

-

-Iinclude/tvisionif your application uses Turbo Vision 1.x includes (#include <tv.h>instead of#include <tvision/tv.h>). -

-Iinclude/tvision/compat/borlandif your application includes Borland headers (dir.h,iostream.h, etc.). -

On Gentoo (and possibly others):

-ltinfowif bothlibtinfo.soandlibtinfow.soare available in your system. Otherwise, you may get a segmentation fault when running Turbo Vision applications (#11). Note thattinfois bundled withncurses.

-lgpm is only necessary if Turbo Vision was built with libgpm support.

The backward-compatibility headers in include/tvision/compat/borland emulate the Borland C++ RTL. Turbo Vision's source code still depends on them, and they could be useful if porting old applications. This also means that including tvision/tv.h will bring several std names to the global namespace.

Windows (MSVC)

The build process with MSVC is slightly more complex, as there are more options to choose from. Note that you will need different build directories for different target architectures. For instance, to generate optimized binaries:

cmake . -B ./build && # Add '-A x64' (64-bit) or '-A Win32' (32-bit) to override the default platform.

cmake --build ./build --config Release # Could also be 'Debug', 'MinSizeRel' or 'RelWithDebInfo'.In the example above, tvision.lib and the example applications will be placed at ./build/Release.

If you wish to link Turbo Vision statically against Microsoft's run-time library (/MT instead of /MD), enable the TV_USE_STATIC_RTL option (-DTV_USE_STATIC_RTL=ON when calling cmake).

If you wish to link an application against Turbo Vision, note that MSVC won't allow you to mix /MT with /MD or debug with non-debug binaries. All components have to be linked against the RTL in the same way.

If you develop your own Turbo Vision application make sure to enable the following compiler flags, or else you will get compilation errors when including <tvision/tv.h>:

/permissive-

/Zc:__cplusplusIf you use Turbo Vision as a CMake submodule, these flags will be enabled automatically.

Note: Turbo Vision uses setlocale to set the RTL functions in UTF-8 mode. This won't work if you use an old version of the RTL.

With the RTL statically linked in, and if UTF-8 is supported in setlocale, Turbo Vision applications are portable and work by default on Windows Vista and later.

Windows (MinGW)

Once your MinGW environment is properly set up, build is done in a similar way to Linux:

cmake . -B ./build -G "MinGW Makefiles" -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release &&

cmake --build ./buildIn the example above, libtvision.a and all examples are in ./build if TV_BUILD_EXAMPLES option is ON (the default).

If you wish to link an application against Turbo Vision, simply add -L./build/lib -ltvision to your linker and -I./include to your compiler

Windows/DOS (Borland C++)

Turbo Vision can still be built either as a DOS or Windows library with Borland C++. Obviously, there is no Unicode support here.

I can confirm the build process works with:

- Borland C++ 4.52 with the Borland PowerPack for DOS.

- Turbo Assembler 4.0.

You may face different problems depending on your build environment. For instance, Turbo Assembler needs a patch to work under Windows 95. On Windows XP everything seems to work fine. On Windows 10, MAKE may emit the error Fatal: Command arguments too long, which can be fixed by upgrading MAKE to the one bundled with Borland C++ 5.x.

Yes, this works on 64-bit Windows 10. What won't work is the Borland C++ installer, which is a 16-bit application. You will have to run it on another environment or try your luck with winevdm.

A Borland Makefile can be found in the project directory. Build can be done by doing:

cd project

make.exe <options>Where <options> can be:

-DDOS32for 32-bit DPMI applications (which still work on 64-bit Windows).-DWIN32for 32-bit native Win32 applications (not possible for TVDEMO, which relies onfarcoreleft()and other antiquities).-DDEBUGto build debug versions of the application and the library.-DTVDEBUGto link the applications with the debug version of the library.-DOVERLAY,-DALIGNMENT={2,4},-DEXCEPTION,-DNO_STREAMABLE,-DNOTASMfor things I have nave never used but appeared in the original makefiles.

This will compile the library into a LIB directory next to project, and will compile executables for the demo applications in their respective examples/* directories.

I'm sorry, the root makefile assumes it is executed from the project directory. You can still run the original makefiles directly (in source/tvision and examples/*) if you want to use different settings.

Vcpkg

Turbo Vision can be built and installed using the vcpkg dependency manager:

git clone https://github.com/Microsoft/vcpkg.git

cd vcpkg

./bootstrap-vcpkg.sh

./vcpkg integrate install

./vcpkg install tvisionThe tvision port in vcpkg is kept up to date by Microsoft team members and community contributors. If you find it to be out of date, please create an issue or pull request in the vcpkg repository.

Turbo Vision as a CMake dependency (not Borland C++)

If you choose the CMake build system for your application, there are two main ways to link against Turbo Vision:

-

Installing Turbo Vision and importing it with

find_package. Installation depends on the generator type:- First, decide an install prefix. The default one will work out-of-the-box, but usually requires admin privileges. On Unix systems, you can use

$HOME/.localinstead. On Windows, you can use any custom path you want but you'll have to add it to theCMAKE_PREFIX_PATHenvironment variable when building your application. -

For mono-config generators (

Unix Makefiles,Ninja...), you only have to build and install once:cmake . -B ./build # '-DCMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX=...' to override the install prefix. cmake --build ./build cmake --install ./build -

For multi-config generators (

Visual Studio,Ninja Multi-Config...) you should build and install all configurations:cmake . -B ./build # '-DCMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX=...' to override the install prefix. cmake --build ./build --config Release cmake --build ./build --config Debug --target tvision cmake --build ./build --config RelWithDebInfo --target tvision cmake --build ./build --config MinSizeRel --target tvision cmake --install ./build --config Release cmake --install ./build --config Debug --component library cmake --install ./build --config RelWithDebInfo --component library cmake --install ./build --config MinSizeRel --component libraryThen, in your application's

CMakeLists.txt, you may import it like this:find_package(tvision CONFIG) target_link_libraries(my_application tvision::tvision)

- First, decide an install prefix. The default one will work out-of-the-box, but usually requires admin privileges. On Unix systems, you can use

-

Have Turbo Vision in a submodule in your repository and import it with

add_subdirectory:add_subdirectory(tvision) # Assuming Turbo Vision is in the 'tvision' directory. target_link_libraries(my_application tvision)

In either case, <tvision/tv.h> will be available in your application's include path during compilation, and your application will be linked against the necessary libraries (Ncurses, GPM...) automatically.

Features

Modern platforms (not Borland C++)

- UTF-8 support. You can try it out in the

tveditapplication. - 24-bit color support (up from the original 16 colors).

- 'Open File' dialogs accepts both Unix and Windows-style file paths and can expand

~/into$HOME. - Redirection of

stdin/stdout/stderrdoes not interfere with terminal I/O. - Compatibility with 32-bit help files.

There are a few environment variables that affect the behaviour of all Turbo Vision applications:

-

TVISION_MAX_FPS: maximum refresh rate, default60. This can help keep smoothness in terminal emulators with unefficient handling of box-drawing characters. Special values for this option are0, to disable refresh rate limiting, and-1, to actually draw to the terminal in every call toTHardwareInfo::screenWrite(useful when debugging). -

TVISION_CODEPAGE: the character set used internally by Turbo Vision to translate extended ASCII into Unicode. Valid values at the moment are437and850, with437being the default, although adding more takes very little effort.

Unix

- Ncurses-based terminal support.

- Extensive mouse and keyboard support:

- Support for X10 and SGR mouse encodings.

- Support for Xterm's modifyOtherKeys.

- Support for Paul Evans' fixterms and Kitty's keyboard protocol.

- Support for Conpty's

win32-input-mode(available in WSL). - Support for far2l's terminal extensions.

- Support for key modifiers (via

TIOCLINUX) and mouse (via GPM) in the Linux console.

- Custom signal handler that restores the terminal state before the program crashes.

- When

stderris a tty, messages written to it are redirected to a buffer to prevent them from messing up the display and are eventually printed to the console when exiting or suspending the application.- The buffer used for this purpose has a limited size, so writes to

stderrwill fail once the buffer is full. If you wish to preserve all ofstderr, just redirect it into a file from the command line with2>.

- The buffer used for this purpose has a limited size, so writes to

The following environment variables are also taken into account:

TERM: Ncurses uses it to determine terminal capabilities. It is set automatically by the terminal emulator.COLORTERM: when set totruecoloror24bit, Turbo Vision will assume the terminal emulator supports 24-bit color. It is set automatically by terminal emulators that support it.ESCDELAY: the number of milliseconds to wait after receiving an ESC key press, default10. If another key is pressed during this delay, it will be interpreted as an Alt+Key combination. Using a larger value is useful when the terminal doesn't support the Alt key.-

TVISION_USE_STDIO: when not empty, terminal I/O is performed throughstdin/stdout, so that it can be redirected from the shell. By default, Turbo Vision performs terminal I/O through/dev/tty, allowing the user to redirectstdin,stdoutandstderrfor their needs, without affecting the application's stability.For example, the following will leave

out.txtempty:tvdemo | tee out.txtWhile the following will dump all the escape sequences and text printed by the application into

out.txt:TVISION_USE_STDIO=1 tvdemo | tee out.txt

Windows

- Only compatible with the Win32 Console API. On terminal emulators that don't support this, Turbo Vision will automatically pop up a separate console window.

- Applications fit the console window size instead of the buffer size (no scrollbars are visible) and the console buffer is restored when exiting or suspending Turbo Vision.

The following are not available when compiling with Borland C++:

- The console's codepage is set to UTF-8 on startup and restored on exit.

- Microsoft's C runtime functions are set automatically to UTF-8 mode, so you as a developer don't need to use the

wchar_tvariants. - If the console crashes, a new one is allocated automatically.

Note: Turbo Vision writes UTF-8 text directly to the Windows console. If the console is set in legacy mode and the bitmap font is being used, Unicode characters will not be displayed properly (photo). To avoid this, Turbo Vision detects this situation and tries to change the console font to Consolas or Lucida Console.

All platforms

The following are new features not available in Borland's release of Turbo Vision or in previous open source ports (Sigala, SET):

- Middle mouse button and mouse wheel support.

- Arbitrary screen size support (up to 32767 rows or columns) and graceful handling of screen resize events.

- Windows can be resized from their bottom left corner.

- Windows can be dragged from empty areas with the middle mouse button.

- Improved usability of menus: they can be closed by clicking again on the parent menu item.

- Improved usability of scrollbars: dragging them also scrolls the page. Clicking on an empty area of the scrollbar moves the thumb right under the cursor. They respond by default to mouse wheel events.

TInputLines no longer scroll the text display on focus/unfocus, allowing relevant text to stay visible.- Support for LF line endings in

TFileViewer(tvdemo) andTEditor(tvedit).TEditorpreserves the line ending on file save but all newly created files use CRLF by default. TEditor: context menu on right click.TEditor: drag scroll with middle mouse button.TEditor,TInputLine: delete whole words withkbAltBack,kbCtrlBackandkbCtrlDel.TEditor: the Home key toggles between beginning of line and beginning of indented text.TEditor: support for files bigger than 64 KiB on 32-bit or 64-bit builds.tvdemo: event viewer applet useful for event debugging.tvdemo: option to change the background pattern.

API changes

- Screen writes are buffered and are usually sent to the terminal once for every iteration of the active event loop (see also

TVISION_MAX_FPS). If you need to update the screen during a busy loop, you may useTScreen::flushScreen(). TDrawBufferis no longer a fixed-length array and its methods prevent past-the-end array accesses. Therefore, old code containing comparisons againstsizeof(TDrawBuffer)/sizeof(ushort)is no longer valid; such checks should be removed.TApplicationnow providesdosShell(),cascade()andtile(), and handlescmDosShell,cmCascadeandcmTileby default. These functions can be customized by overridinggetTileRect()andwriteShellMsg(). This is the same behaviour as in the Pascal version.- Mouse wheel support: new mouse event

evMouseWheel. The wheel direction is specified in the new fieldevent.mouse.wheel, whose possible values aremwUp,mwDown,mwLeftormwRight. - Middle mouse button support: new mouse button flag

mbMiddleButton. - The

buttonsfield inevMouseUpevents is no longer empty. It now indicates which button was released. - Triple-click support: new mouse event flag

meTripleClick. TRectmethodsmove,grow,intersectandUnionnow returnTRect&instead of beingvoidso that they can be chained.TOutlineViewernow allows the root node to have siblings.- New function

ushort popupMenu(TPoint where, TMenuItem &aMenu, TGroup *receiver=0)which spawns aTMenuPopupon the desktop. Seesource/tvision/popupmnu.cpp. - New virtual method

TMenuItem& TEditor::initContextMenu(TPoint p)that determines the entries of the right-click context menu inTEditor. fexpandcan now take a second parameterrelativeTo.- New class

TStringView, inspired bystd::string_view.- Many functions which originally had null-terminated string parameters now receive

TStringViewinstead.TStringViewis compatible withstd::string_view,std::stringandconst char *(evennullptr).

- Many functions which originally had null-terminated string parameters now receive

- New class

TSpan<T>, inspired bystd::span. - New classes

TDrawSurfaceandTSurfaceView, see<tvision/surface.h>. - The system integration subsystems (

THardwareInfo,TScreen,TEventQueue...) are now initialized when constructing aTApplicationfor the first time, rather than beforemain. They are still destroyed on exit frommain. - New method

TVMemMgr::reallocateDiscardable()which can be used alongallocateDiscardableandfreeDiscardable. - New method

TView::textEvent()which allows receiving text in an efficient manner, see Clipboard interaction. - New class

TClipboard, see Clipboard interaction. - Unicode support, see Unicode.

- True Color support, see extended colors.

- New method

static void TEventQueue::waitForEvents(int timeoutMs)which may block for up totimeoutMsmilliseconds waiting for input events. A negativetimeoutMscan be used to wait undefinitely. If it blocks, it has the side effect of flushing screen updates (viaTScreen::flushScreen()). It is invoked byTProgram::getEvent()withstatic int TProgram::eventTimeoutMs(default20) as argument so that the event loop does not turn into a busy loop consuming 100% CPU. - New method

static void TEventQueue::wakeUp()which causes the event loop to resume execution if it is blocked atTEventQueue::waitForEvents(). This method is thread-safe, since its purpose is to unblock the event loop from secondary threads. - New method

void TView::getEvent(TEvent &, int timeoutMs)which allows waiting for an event with an user-provided timeout (instead ofTProgram::eventTimeoutMs). - It is now possible to specify a maximum text width or maximum character count in

TInputLine. This is done through a new parameter inTInputLine's constructor,ushort limitMode, which controls how the second constructor parameter,uint limit, is to be treated. TheilXXXXconstants define the possible values oflimitMode:ilMaxBytes(the default): the text can be up tolimitbytes long, including the null terminator.ilMaxWidth: the text can be up tolimitcolumns wide.ilMaxChars: the text can contain up tolimitnon-combining characters or graphemes.

- New functions which allow getting the names of Turbo Vision's constants at runtime (e.g.

evCommand,kbShiftIns, etc.):void printKeyCode(ostream &, ushort keyCode); void printControlKeyState(ostream &, ushort controlKeyState); void printEventCode(ostream &, ushort eventCode); void printMouseButtonState(ostream &, ushort buttonState); void printMouseWheelState(ostream &, ushort wheelState); void printMouseEventFlags(ostream &, ushort eventFlags); - New class

TKeywhich can be used to define new key combinations (e.g.Shift+Alt+Up) by specifying a key code and a mask of key modifiers:auto kbShiftAltUp = TKey(kbUp, kbShift | kbAltShift); assert(kbCtrlA == TKey('A', kbCtrlShift)); assert(TKey(kbCtrlTab, kbShift) == TKey(kbTab, kbShift | kbCtrlShift)); // Create menu hotkeys. new TMenuItem("~R~estart", cmRestart, TKey(kbDel, kbCtrlShift | kbAltShift), hcNoContext, "Ctrl-Alt-Del") // Examine KeyDown events: if (event.keyDown == TKey(kbEnter, kbShift)) doStuff(); -

New methods which allow using timed events:

TTimerId TView::setTimer(uint timeoutMs, int periodMs = -1); void TView::killTimer(TTimerId id);setTimerstarts a timer that will first time out intimeoutMsmilliseconds and then everyperiodMsmilliseconds.If

periodMsis negative, the timer only times out a single time and is cleaned up automatically. Otherwise, it will keep timing out periodically untilkillTimeris invoked.When a timer times out, an

evBroadcastevent with the commandcmTimerExpiredis emitted, andmessage.infoPtris set to theTTimerIdof the expired timer.Timeout events are generated in

TProgram::idle(). Therefore, they are only processed when no keyboard or mouse events are available.

Screenshots

You will find some screenshots here. Feel free to add your own!

Contributing

If you know of any Turbo Vision applications whose source code has not been lost and that could benefit from this, let me know.

Applications using Turbo Vision

If your application is based on this project and you'd like it to appear in the following list, just let me know.

- Turbo by magiblot, a proof-of-concept text editor.

- tvterm by magiblot, a proof-of-concept terminal emulator.

- TMBASIC by Brian Luft, a programming language for creating console applications.

Unicode support

The Turbo Vision API has been extended to allow receiving Unicode input and displaying Unicode text. The supported encoding is UTF-8, for a number of reasons:

- It is compatible with already present data types (

char *), so it does not require intrusive modifications to existing code. - It is the same encoding used for terminal I/O, so redundant conversions are avoided.

- Conformance to the UTF-8 Everywhere Manifesto, which exposes many other advantages.

Note that when built with Borland C++, Turbo Vision does not support Unicode. However, this does not affect the way Turbo Vision applications are written, since the API extensions are designed to allow for encoding-agnostic code.

Reading Unicode input

The traditional way to get text from a key press event is as follows:

// 'ev' is a TEvent, and 'ev.what' equals 'evKeyDown'.

switch (ev.keyDown.keyCode) {

// Key shortcuts are usually checked first.

// ...

default: {

// The character is encoded in the current codepage

// (CP437 by default).

char c = ev.keyDown.charScan.charCode;

// ...

}

}Some of the existing Turbo Vision classes that deal with text input still depend on this methodology, which has not changed. Single-byte characters, when representable in the current codepage, continue to be available in ev.keyDown.charScan.charCode.

Unicode support consists in two new fields in ev.keyDown (which is a struct KeyDownEvent):

char text[4], which may contain whatever was read from the terminal: usually a UTF-8 sequence, but possibly any kind of raw data.uchar textLength, which is the number of bytes of data available intext, from 0 to 4.

Note that the text string is not null-terminated.

You can get a TStringView out of a KeyDownEvent with the getText() method.

So a Unicode character can be retrieved from TEvent in the following way:

switch (ev.keyDown.keyCode) {

// ...

default: {

std::string_view sv = ev.keyDown.getText();

processText(sv);

}

}Let's see it from another perspective. If the user types ñ, a TEvent is generated with the following keyDown struct:

KeyDownEvent {

union {

.keyCode = 0xA4,

.charScan = CharScanType {

.charCode = 164 ('ñ'), // In CP437

.scanCode = 0

}

},

.controlKeyState = 0x200 (kbInsState),

.text = {'\xC3', '\xB1'}, // In UTF-8

.textLength = 2

}However, if they type € the following will happen:

KeyDownEvent {

union {

.keyCode = 0x0 (kbNoKey), // '€' not part of CP437

.charScan = CharScanType {

.charCode = 0,

.scanCode = 0

}

},

.controlKeyState = 0x200 (kbInsState),

.text = {'\xE2', '\x82', '\xAC'}, // In UTF-8

.textLength = 3

}If a key shortcut is pressed instead, text is empty:

KeyDownEvent {

union {

.keyCode = 0xB (kbCtrlK),

.charScan = CharScanType {

.charCode = 11 ('♂'),

.scanCode = 0

}

},

.controlKeyState = 0x20C (kbCtrlShift | kbInsState),

.text = {},

.textLength = 0

}So, in short: views designed without Unicode input in mind will continue to work exactly as they did before, and views which want to be Unicode-aware will have no issues in being so.

Displaying Unicode text

The original design of Turbo Vision uses 16 bits to represent a screen cell—8 bit for a character and 8 bit for BIOS color attributes.

A new TScreenCell type is defined in <tvision/scrncell.h> which is capable of holding a limited number of UTF-8 codepoints in addition to extended attributes (bold, underline, italic...). However, you should not write text into a TScreenCell directly but make use of Unicode-aware API functions instead.

Text display rules

A character provided as argument to any of the Turbo Vision API functions that deal with displaying text is interpreted as follows:

- Non-printable characters in the range

0x00to0xFFare interpreted as characters in the active codepage. For instance,0x7Fis displayed as⌂and0xF0as≡if using CP437. As an exception,0x00is always displayed as a regular space. These characters are all one column wide. - Character sequences which are not valid UTF-8 are interpreted as sequences of characters in the current codepage, as in the case above.

- Valid UTF-8 sequences with a display width other than one are taken care of in a special way, see below.

For example, the string "╔[\xFE]╗" may be displayed as ╔[■]╗. This means that box-drawing characters can be mixed with UTF-8 in general, which is useful for backward compatibility. If you rely on this behaviour, though, you may get unexpected results: for instance, "\xC4\xBF" is a valid UTF-8 sequence and is displayed as Ŀ instead of ─┐.

One of the issues of Unicode support is the existence of double-width characters and combining characters. This conflicts with Turbo Vision's original assumption that the screen is a grid of cells occupied by a single character each. Nevertheless, these cases are handled in the following way:

- Double-width characters can be drawn anywhere on the screen and nothing bad happens if they overlap partially with other characters.

-

Zero-width characters overlay the previous character. For example, the sequence

मेंconsists of the single-width characterमand the combining charactersेandं. In this case, three Unicode codepoints are fit into the same cell.The

ZERO WIDTH JOINER(U+200D) is always omitted, as it complicates things too much. For example, it can turn a string like"👩👦"(4 columns wide) into"👩👦"(2 columns wide). Not all terminal emulators respect the ZWJ, so, in order to produce predictable results, Turbo Vision will print both"👩👦"and"👩👦"as👩👦. - No notable graphical glitches will occur as long as your terminal emulator respects character widths as measured by

wcwidth.

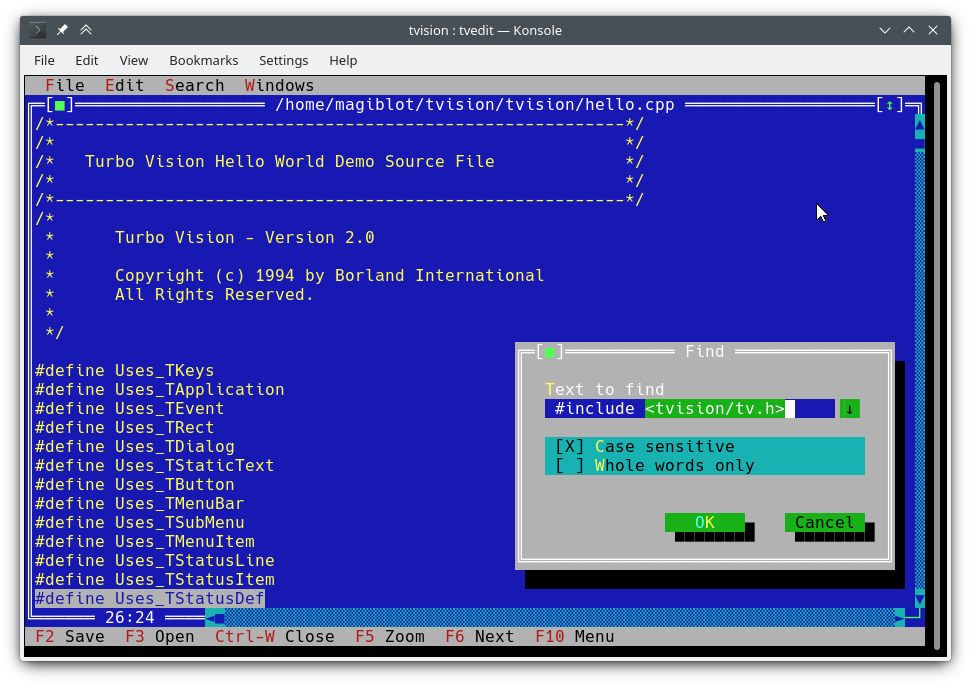

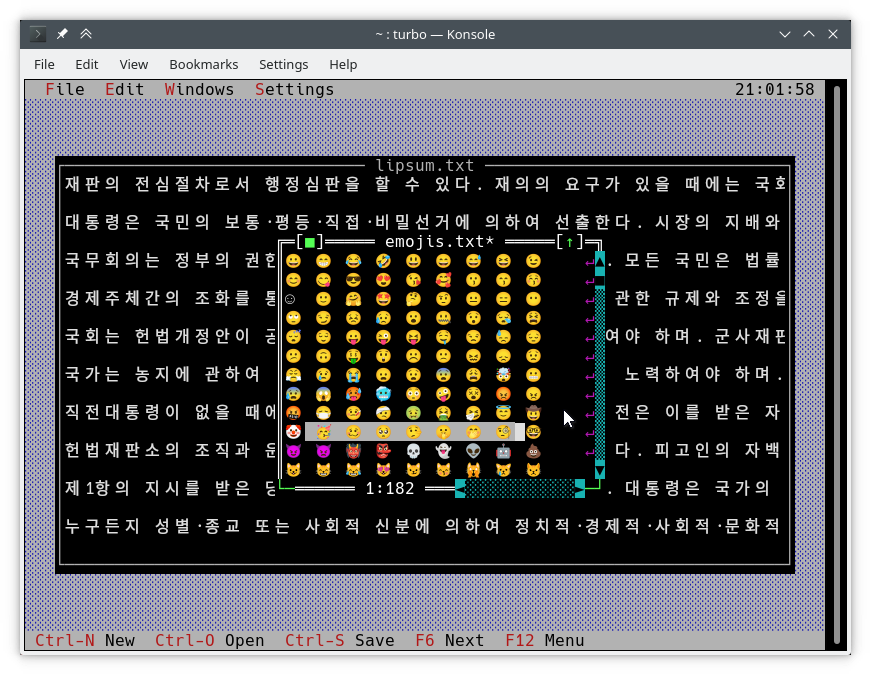

Here is an example of such characters in the Turbo text editor:

Unicode-aware API functions

The usual way of writing to the screen is by using TDrawBuffer. A few methods have been added and others have changed their meaning:

void TDrawBuffer::moveChar(ushort indent, char c, TColorAttr attr, ushort count);

void TDrawBuffer::putChar(ushort indent, char c);c is always interpreted as a character in the active codepage.

ushort TDrawBuffer::moveStr(ushort indent, TStringView str, TColorAttr attr);

ushort TDrawBuffer::moveCStr(ushort indent, TStringView str, TAttrPair attrs);str is interpreted according to the rules exposed previously.

ushort TDrawBuffer::moveStr(ushort indent, TStringView str, TColorAttr attr, ushort maxWidth, ushort strOffset = 0); // New

ushort TDrawBuffer::moveCStr(ushort indent, TStringView str, TColorAttr attr, ushort maxWidth, ushort strOffset = 0); // Newstr is interpreted according to the rules exposed previously, but:

maxWidthspecifies the maximum amount of text that should be copied fromstr, measured in text width (not in bytes).strOffsetspecifies the initial position instrwhere to copy from, measured in text width (not in bytes). This is useful for horizontal scrolling. IfstrOffsetpoints to the middle of a double-width character, a space will be copied instead of the right half of the double-width character, since it is not possible to do such a thing.

The return values are the number of cells in the buffer that were actually filled with text (which is the same as the width of the copied text).

void TDrawBuffer::moveBuf(ushort indent, const void *source, TColorAttr attr, ushort count);The name of this function is misleading. Even in its original implementation, source is treated as a string. So it is equivalent to moveStr(indent, TStringView((const char*) source, count), attr).

There are other useful Unicode-aware functions:

int cstrlen(TStringView s);Returns the displayed length of s according to the aforementioned rules, discarding ~ characters.

int strwidth(TStringView s); // NewReturns the displayed length of s.

On Borland C++, these methods assume a single-byte encoding and all characters being one column wide. This makes it possible to write encoding-agnostic draw() and handleEvent() methods that work on both platforms without a single #ifdef.

The functions above are implemented using the functions from the TText namespace, another API extension. You will have to use them directly if you want to fill TScreenCell objects with text manually. To give an example, below are some of the TText functions. You can find all of them with complete descriptions in <tvision/ttext.h>.

size_t TText::next(TStringView text);

size_t TText::prev(TStringView text, size_t index);

void TText::drawChar(TSpan<TScreenCell> cells, char c);

size_t TText::drawStr(TSpan<TScreenCell> cells, size_t indent, TStringView text, int textIndent);

bool TText::drawOne(TSpan<TScreenCell> cells, size_t &i, TStringView text, size_t &j);For drawing TScreenCell buffers into a view, the following methods are available:

void TView::writeBuf(short x, short y, short w, short h, const TScreenCell *b); // New

void TView::writeLine(short x, short y, short w, short h, const TScreenCell *b); // NewExample: Unicode text in menus and status bars

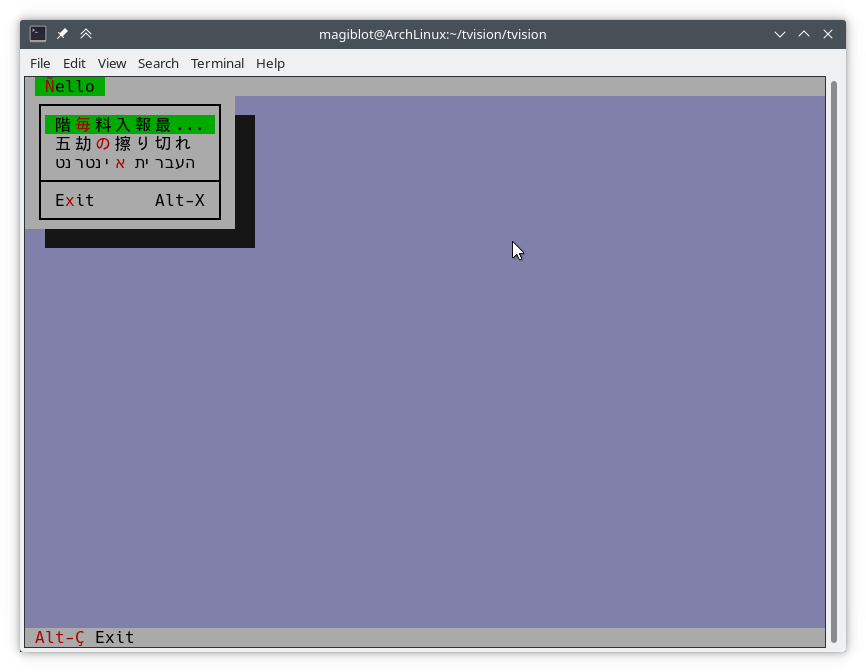

It's as simple as it can be. Let's modify hello.cpp as follows:

TMenuBar *THelloApp::initMenuBar( TRect r )

{

r.b.y = r.a.y+1;

return new TMenuBar( r,

*new TSubMenu( "~Ñ~ello", kbAltH ) +

*new TMenuItem( "階~毎~料入報最...", GreetThemCmd, kbAltG ) +

*new TMenuItem( "五劫~の~擦り切れ", cmYes, kbNoKey, hcNoContext ) +

*new TMenuItem( "העברית ~א~ינטרנט", cmNo, kbNoKey, hcNoContext ) +

newLine() +

*new TMenuItem( "E~x~it", cmQuit, cmQuit, hcNoContext, "Alt-X" )

);

}

TStatusLine *THelloApp::initStatusLine( TRect r )

{

r.a.y = r.b.y-1;

return new TStatusLine( r,

*new TStatusDef( 0, 0xFFFF ) +

*new TStatusItem( "~Alt-Ç~ Exit", kbAltX, cmQuit ) +

*new TStatusItem( 0, kbF10, cmMenu )

);

}Here is what it looks like:

Example: writing Unicode-aware draw() methods

The following is an excerpt from an old implementation of TFileViewer::draw() (part of the tvdemo application), which does not draw Unicode text properly:

if (delta.y + i < fileLines->getCount()) {

char s[maxLineLength+1];

p = (char *)(fileLines->at(delta.y+i));

if (p == 0 || strlen(p) < delta.x)

s[0] = EOS;

else

strnzcpy(s, p+delta.x, maxLineLength+1);

b.moveStr(0, s, c);

}

writeBuf( 0, i, size.x, 1, b );All it does is move part of a string in fileLines into b, which is a TDrawBuffer. delta is a TPoint representing the scroll offset in the text view, and i is the index of the visible line being processed. c is the text color. A few issues are present:

TDrawBuffer::moveStr(ushort, const char *, TColorAttr)takes a null-terminated string. In order to pass a substring of the current line, a copy is made into the arrays, at the risk of a buffer overrun. The case where the line does not fit intosis not handled, so at mostmaxLineLenghtcharacters will be copied. What's more, a multibyte character near positionmaxLineLengthcould be copied incompletely and be displayed as garbage.delta.xis the first visible column. With multibyte-encoded text, it is no longer true that such column begins at positiondelta.xin the string.

Below is a corrected version of the code above that handles Unicode properly:

if (delta.y + i < fileLines->getCount()) {

p = (char *)(fileLines->at(delta.y+i));

if (p)

b.moveStr(0, p, c, size.x, delta.x);

}

writeBuf( 0, i, size.x, 1, b );The overload of moveStr used here is TDrawBuffer::moveStr(ushort indent, TStringView str, TColorAttr attr, ushort width, ushort begin). This function not only provides Unicode support, but also helps us write cleaner code and overcome some of the limitations previously present:

- The intermediary copy is avoided, so the displayed text is not limited to

maxLineLengthbytes. moveStrtakes care of printing the string starting at columndelta.x. We do not even need to worry about how many bytes correspond todelta.xcolumns.- Similarly,

moveStris instructed to copy at mostsize.xcolumns of text without us having to care about how many bytes that is nor dealing with edge cases. The code is written in an encoding-agnostic way and will work whether multibyte characters are being considered or not. - In case you hadn't realized yet, the intermediary copy in the previous version was completely unnecessary. It would have been necessary only if we had needed to trim the end of the line, but that was not the case: text occupies all of the view's width, and

TView::writeBufalready takes care of not writing beyond it. Yet it is interesting to see how an unnecessary step not only was limiting functionality but also was prone to bugs.

Unicode support across standard views

Support for creating Unicode-aware views is in place, and most views in the original Turbo Vision library have been adapted to handle Unicode.

The following views can display Unicode text properly. Some of them also do horizontal scrolling or word wrapping; all of that should work fine.

- [x]

TStaticText(7b15d45d). - [x]

TFrame(81066ee5). - [x]

TStatusLine(477b3ae9). - [x]

THistoryViewer(81066ee5). - [x]

THelpViewer(81066ee5,8c7dac2a,20f331e3). - [x]

TListViewer(81066ee5). - [x]

TMenuBox(81066ee5). - [x]

TTerminal(ee821b69). - [x]

TOutlineViewer(6cc8cd38). - [x]

TFileViewer(from thetvdemoapplication) (068bbf7a). - [x]

TFilePane(from thetvdirapplication) (9bcd897c).

The following views can, in addition, process Unicode text or user input:

- [x]

TInputLine(81066ee5,cb489d42). - [x]

TEditor(702114dc). Instances are in UTF-8 mode by default. You may switch back to single-byte mode by pressingCtrl+P. This only changes how the document is displayed and the encoding of user input; it does not alter the document. This class is used in thetveditapplication; you may test it there.

Views not in this list may not have needed any corrections or I simply forgot to fix them. Please submit an issue if you notice anything not working as expected.

Use cases where Unicode is not supported (not an exhaustive list):

- [ ] Highlighted key shortcuts, in general (e.g.

TMenuBox,TStatusLine,TButton...).

Clipboard interaction

Originally, Turbo Vision offered no integration with the system clipboard, since there was no such thing on MS-DOS.

It did offer the possibility of using an instance of TEditor as an internal clipboard, via the TEditor::clipboard static member. However, TEditor was the only class able to interact with this clipboard. It was not possible to use it with TInputLine, for example.

Turbo Vision applications are now most likely to be ran in a graphical environment through a terminal emulator. In this context, it would be desirable to interact with the system clipboard in the same way as a regular GUI application would do.

To deal with this, a new class TClipboard has been added which allows accessing the system clipboard. If the system clipboard is not accessible, it will instead use an internal clipboard.

Enabling clipboard support

On Windows (including WSL) and macOS, clipboard integration is supported out-of-the-box.

On Unix systems other than macOS, it is necessary to install some external dependencies. See runtime requirements.

For applications running remotely (e.g. through SSH), clipboard integration is supported in the following situations:

- When X11 forwarding over SSH is enabled (

ssh -X). - When your terminal emulator supports far2l's terminal extensions (far2l, putty4far2l).

- When your terminal emulator supports OSC 52 escape codes:

Additionally, it is always possible to paste text using your terminal emulator's own Paste command (usually Ctrl+Shift+V or Cmd+V).

API usage

To use the TClipboard class, define the macro Uses_TClipboard before including <tvision/tv.h>.

Writing to the clipboard

static void TClipboard::setText(TStringView text);Sets the contents of the system clipboard to text. If the system clipboard is not accessible, an internal clipboard is used instead.

Reading the clipboard

static void TClipboard::requestText();Requests the contents of the system clipboard asynchronously, which will be later received in the form of regular evKeyDown events. If the system clipboard is not accessible, an internal clipboard is used instead.

Processing Paste events

A Turbo Vision application may receive a Paste event for two different reasons:

- Because

TClipboard::requestText()was invoked. - Because the user pasted text through the terminal.

In both cases the application will receive the clipboard contents in the form of regular evKeyDown events. These events will have a kbPaste flag in keyDown.controlKeyState so that they can be distinguished from regular key presses.

Therefore, if your view can handle user input it will also handle Paste events by default. However, if the user pastes 5000 characters, the application will behave as if the user pressed the keyboard 5000 times. This involves drawing views, completing the event loop, updating the screen..., which is far from optimal if your view is a text editing component, for example.

For the purpose of dealing with this situation, another function has been added:

bool TView::textEvent(TEvent &event, TSpan<char> dest, size_t &length);textEvent() attempts to read text from consecutive evKeyDown events and stores it in a user-provided buffer dest. It returns false when no more events are available or if a non-text event is found, in which case this event is saved with putEvent() so that it can be processed in the next iteration of the event loop. Finally, it calls clearEvent(event).

The exact number of bytes read is stored in the output parameter length, which will never be larger than dest.size().

Here is an example on how to use it:

// 'ev' is a TEvent, and 'ev.what' equals 'evKeyDown'.

// If we received text from the clipboard...

if (ev.keyDown.controlKeyState & kbPaste) {

char buf[512];

size_t length;

// Fill 'buf' with the text in 'ev' and in

// upcoming events from the input queue.

while (textEvent(ev, buf, length)) {

// Process 'length' bytes of text in 'buf'...

}

}Enabling application-wide clipboard usage

The standard views TEditor and TInputLine react to the cmCut, cmCopy and cmPaste commands. However, your application first has to be set up to use these commands. For example:

TStatusLine *TMyApplication::initStatusLine( TRect r )

{

r.a.y = r.b.y - 1;

return new TStatusLine( r,

*new TStatusDef( 0, 0xFFFF ) +

// ...

*new TStatusItem( 0, kbCtrlX, cmCut ) +

*new TStatusItem( 0, kbCtrlC, cmCopy ) +

*new TStatusItem( 0, kbCtrlV, cmPaste ) +

// ...

);

}TEditor and TInputLine automatically enable and disable these commands. For example, if a TEditor or TInputLine is focused, the cmPaste command will be enabled. If there is selected text, the cmCut and cmCopy commands will also be enabled. If no TEditor or TInputLines are focused, then these commands will be disabled.

Extended color support

The Turbo Vision API has been extended to allow more than the original 16 colors.

Colors can be specified using any of the following formats:

- BIOS color attributes (4-bit), the format used originally on MS-DOS.

- RGB (24-bit).

xterm-256colorpalette indices (8-bit).- The terminal default color. This is the color used by terminal emulators when no display attributes (bold, color...) are enabled (usually white for foreground and black for background).

Although Turbo Vision applications are likely to be ran in a terminal emulator, the API makes no assumptions about the display device. That is to say, the complexity of dealing with terminal emulators is hidden from the programmer and managed by Turbo Vision itself.

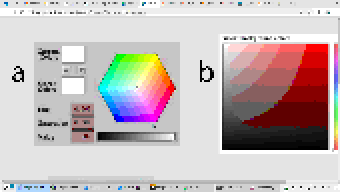

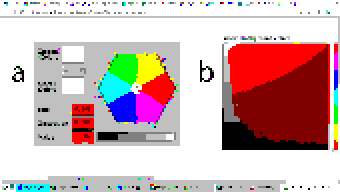

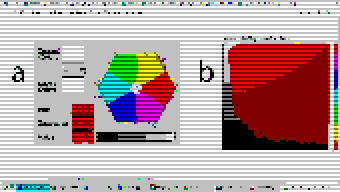

For example: color support varies among terminals. If the programmer uses a color format not supported by the terminal emulator, Turbo Vision will quantize it to what the terminal can display. The following images represent the quantization of a 24-bit RGB picture to 256, 16 and 8 color palettes:

| 24-bit color (original) | 256 colors |

|---|---|

|

|

| 16 colors | 8 colors (bold as bright) |

|---|---|

|

|

Extended color support basically comes down to the following:

- Turbo Vision has originally used BIOS color attributes stored in an

uchar.ushortis used to represent attribute pairs. This is still the case when using Borland C++. - In modern platforms a new type

TColorAttrhas been added which replacesuchar. It specifies a foreground and background color and a style. Colors can be specified in different formats (BIOS color attributes, 24-bit RGB...). Styles are the typical ones (bold, italic, underline...). There's alsoTAttrPair, which replacesushort. TDrawBuffer's methods, which used to takeucharorushortparameters to specify color attributes, now takeTColorAttrorTAttrPair.TPalette, which used to contain an array ofuchar, now contains an array ofTColorAttr. TheTView::mapColormethod also returnsTColorAttrinstead ofuchar.TView::mapColorhas been made virtual so that the palette system can be bypassed without having to rewrite anydrawmethods.TColorAttrandTAttrPaircan be initialized with and casted intoucharandushortin a way such that legacy code still compiles out-of-the-box without any change in functionality.

Below is a more detailed explanation aimed at developers.

Data Types

In the first place we will explain the data types the programmer needs to know in order to take advantage of the extended color support. To get access to them, you may have to define the macro Uses_TColorAttr before including <tvision/tv.h>.

All the types described in this section are trivial. This means that they can be memset'd and memcpy'd. But variables of these types are uninitialized when declared without initializer, just like primitive types. So make sure you don't manipulate them before initializing them.

Color format types

Several types are defined which represent different color formats. The reason why these types exist is to allow distinguishing color formats using the type system. Some of them also have public fields which make it easier to manipulate individual bits.

-

TColorBIOSrepresents a BIOS color. It allows accessing ther,g,bandbrightbits individually, and can be casted implicitly into/fromuint8_t.The memory layout is:

- Bit 0: Blue (field

b). - Bit 1: Green (field

g). - Bit 2: Red (field

r). - Bit 3: Bright (field

bright). - Bits 4-7: unused.

Examples of

TColorBIOSusage:TColorBIOS bios = 0x4; // 0x4: red. bios.bright = 1; // 0xC: light red. bios.b = bios.r; // 0xD: light magenta. bios = bios ^ 3; // 0xE: yellow. uint8_t c = bios; // Implicit conversion to integer types.In terminal emulators, BIOS colors are mapped to the basic 16 ANSI colors.

- Bit 0: Blue (field

-

TColorRGBrepresents a color in 24-bit RGB. It allows accessing ther,gandbbit fields individually, and can be casted implicitly into/fromuint32_t.The memory layout is:

- Bits 0-7: Blue (field

b). - Bits 8-15: Green (field

g). - Bits 16-23: Red (field

r). - Bits 24-31: unused.

Examples of

TColorRGBusage:TColorRGB rgb = 0x9370DB; // 0xRRGGBB. rgb = {0x93, 0x70, 0xDB}; // {R, G, B}. rgb = rgb ^ 0xFFFFFF; // Negated. rgb.g = rgb.r & 0x88; // Access to individual components. uint32_t c = rgb; // Implicit conversion to integer types. - Bits 0-7: Blue (field

-

TColorXTermrepresents an index into thexterm-256colorcolor palette. It can be casted into and fromuint8_t.

TColorDesired

TColorDesired represents a color which the programmer intends to show on screen, encoded in any of the supported color types.

A TColorDesired can be initialized in the following ways:

-

As a BIOS color: with a

charliteral or aTColorBIOSobject:TColorDesired bios1 = '\xF'; TColorDesired bios2 = TColorBIOS(0xF); -

As a RGB color: with an

intliteral or aTColorRGBobject:TColorDesired rgb1 = 0xFF7700; // 0xRRGGBB. TColorDesired rgb2 = TColorRGB(0xFF, 0x77, 0x00); // {R, G, B}. TColorDesired rgb3 = TColorRGB(0xFF7700); // 0xRRGGBB. - As an XTerm palette index: with a

TColorXTermobject. -

As the terminal default color: through zero-initialization:

TColorDesired def1 {}; // Or with 'memset': TColorDesired def2; memset(&def2, 0, sizeof(def2));

TColorDesired has methods to query the contained color, but you will usually not need to use them. See the struct definition in <tvision/colors.h> for more information.

Trivia: the name is inspired by Scintilla's ColourDesired.

TColorAttr

TColorAttr describes the color attributes of a screen cell. This is the type you are most likely to interact with if you intend to change the colors in a view.

A TColorAttr is composed of:

- A foreground color, of type

TColorDesired. - A background color, of type

TColorDesired. -

A style bitmask containing a combination of the following flags:

slBold.slItalic.slUnderline.slBlink.slReverse.slStrike.

These flags are based on the basic display attributes selectable through ANSI escape codes. The results may vary between terminal emulators.

slReverseis probably the least reliable of them: prefer using theTColorAttr reverseAttribute(TColorAttr attr)free function over setting this flag.

The most straight-forward way to create a TColorAttr is by means of the TColorAttr(TColorDesired fg, TColorDesired bg, ushort style=0) and TColorAttr(int bios) constructors:

// Foreground: RGB 0x892312

// Background: RGB 0x7F00BB

// Style: Normal.

TColorAttr a1 = {TColorRGB(0x89, 0x23, 0x12), TColorRGB(0x7F, 0x00, 0xBB)};

// Foreground: BIOS 0x7.

// Background: RGB 0x7F00BB.

// Style: Bold, Italic.

TColorAttr a2 = {'\x7', 0x7F00BB, slBold | slItalic};

// Foreground: Terminal default.

// Background: BIOS 0xF.

// Style: Normal.

TColorAttr a3 = {{}, TColorBIOS(0xF)};

// Foreground: Terminal default.

// Background: Terminal default.

// Style: Normal.

TColorAttr a4 = {};

// Foreground: BIOS 0x0

// Background: BIOS 0x7

// Style: Normal

TColorAttr a5 = 0x70;The fields of a TColorAttr can be accessed with the following free functions:

TColorDesired getFore(const TColorAttr &attr);

TColorDesired getBack(const TColorAttr &attr);

ushort getStyle(const TColorAttr &attr);

void setFore(TColorAttr &attr, TColorDesired fg);

void setBack(TColorAttr &attr, TColorDesired bg);

void setStyle(TColorAttr &attr, ushort style);TAttrPair

TAttrPair is a pair of TColorAttr, used by some API functions to pass two attributes at once.

You may initialize a TAttrPair with the TAttrPair(const TColorAttrs &lo, const TColorAttrs &hi) constructor:

TColorAttr cNormal = {0x234983, 0x267232};

TColorAttr cHigh = {0x309283, 0x127844};

TAttrPair attrs = {cNormal, cHigh};

TDrawBuffer b;

b.moveCStr(0, "Normal text, ~Highlighted text~", attrs);The attributes can be accessed with the [0] and [1] subindices:

TColorAttr lo = {0x892343, 0x271274};

TColorAttr hi = '\x93';

TAttrPair attrs = {lo, hi};

assert(lo == attrs[0]);

assert(hi == attrs[1]);Changing the appearance of a TView

Views are commonly drawn by means of a TDrawBuffer. Most TDrawBuffer member functions take color attributes by parameter. For example:

ushort TDrawBuffer::moveStr(ushort indent, TStringView str, TColorAttr attr);

ushort TDrawBuffer::moveCStr(ushort indent, TStringView str, TAttrPair attrs);

void TDrawBuffer::putAttribute(ushort indent, TColorAttr attr);However, the views provided with Turbo Vision usually store their color information in palettes. A view's palette can be queried with the following member functions:

TColorAttr TView::mapColor(uchar index);

TAttrPair TView::getColor(ushort indices);-

mapColorlooks up a single color attribute in the view's palette, given an index into the palette. Remember that the palette indices for each view class can be found in the Turbo Vision headers. For example,<tvision/views.h>says the following aboutTScrollBar:/* ---------------------------------------------------------------------- */ /* class TScrollBar */ /* */ /* Palette layout */ /* 1 = Page areas */ /* 2 = Arrows */ /* 3 = Indicator */ /* ---------------------------------------------------------------------- */ -

getColoris a helper function that allows querying two cell attributes at once. Each byte in theindicesparameter contains an index into the palette. TheTAttrPairresult contains the two cell attributes.For example, the following can be found in the

drawmethod ofTMenuBar:TAttrPair cNormal = getColor(0x0301); TAttrPair cSelect = getColor(0x0604);Which would be equivalent to this:

TAttrPair cNormal = {mapColor(1), mapColor(3)}; TAttrPair cSelect = {mapColor(4), mapColor(6)};

As an API extension, the mapColor method has been made virtual. This makes it possible to override Turbo Vision's hierarchical palette system with a custom solution without having to rewrite the draw() method.

So, in general, there are three ways to use extended colors in views:

- By returning extended color attributes from an overridden

mapColormethod:

// The 'TMyScrollBar' class inherits from 'TScrollBar' and overrides 'TView::mapColor'.

TColorAttr TMyScrollBar::mapColor(uchar index) noexcept

{

// In this example the values are hardcoded,

// but they could be stored elsewhere if desired.

switch (index)

{

case 1: return {0x492983, 0x826124}; // Page areas.

case 2: return {0x438939, 0x091297}; // Arrows.

case 3: return {0x123783, 0x329812}; // Indicator.

default: return errorAttr;

}

}-

By providing extended color attributes directly to

TDrawBuffermethods, if the palette system is not being used. For example:// The 'TMyView' class inherits from 'TView' and overrides 'TView::draw'. void TMyView::draw() { TDrawBuffer b; TColorAttr color {0x1F1C1B, 0xFAFAFA, slBold}; b.moveStr(0, "This is bold black text over a white background", color); /* ... */ } -

By modifying the palettes. There are two ways to do this:

- By modifying the application palette after it has been built. Note that the palette elements are

TColorAttr. For example:

void updateAppPalette() { TPalette &pal = TProgram::application->getPalete(); pal[1] = {0x762892, 0x828712}; // TBackground. pal[2] = {0x874832, 0x249838, slBold}; // TMenuView normal text. pal[3] = {{}, {}, slItalic | slUnderline}; // TMenuView disabled text. /* ... */ }- By using extended color attributes in the application palette definition:

static const TColorAttr cpMyApp[] = { {0x762892, 0x828712}, // TBackground. {0x874832, 0x249838, slBold}, // TMenuView normal text. {{}, {}, slItalic | slUnderline}, // TMenuView disabled text. /* ... */ }; // The 'TMyApp' class inherits from 'TApplication' and overrides 'TView::getPalette'. TPalette &TMyApp::getPalette() const { static TPalette palette(cpMyApp); return palette; } - By modifying the application palette after it has been built. Note that the palette elements are

Display capabilities

TScreen::screenMode exposes some information about the display's color support:

- If

(TScreen::screenMode & 0xFF) == TDisplay::smMono, the display is monocolor (only relevant in DOS). - If

(TScreen::screenMode & 0xFF) == TDisplay::smBW80, the display is grayscale (only relevant in DOS). - If

(TScreen::screenMode & 0xFF) == TDisplay::smCO80, the display supports at least 16 colors.- If

TScreen::screenMode & TDisplay::smColor256, the display supports at least 256 colors. - If

TScreen::screenMode & TDisplay::smColorHigh, the display supports even more colors (e.g. 24-bit color).TDisplay::smColor256is also set in this case.

- If

Backward-compatibility of color types

The types defined previously represent concepts that are also important when developing for Borland C++:

| Concept | Layout in Borland C++ | Layout in modern platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Color Attribute | uchar. A BIOS color attribute. |

struct TColorAttr. |

| Color | A 4-bit number. | struct TColorDesired. |

| Attribute Pair | ushort. An attribute in each byte. |

struct TAttrPair. |

One of this project's key principles is that the API should be used in the same way both in Borland C++ and modern platforms, that is to say, without the need for #ifdefs. Another principle is that legacy code should compile out-of-the-box, and adapting it to the new features should increase complexity as little as possible.

Backward-compatibility is accomplished in the following way:

- In Borland C++,

TColorAttrandTAttrPairaretypedef'd toucharandushort, respectively. -

In modern platforms,

TColorAttrandTAttrPaircan be used in place ofucharandushort, respectively, since they are able to hold any value that fits into them and can be casted implicitly into/from them.A

TColorAttrinitialized withucharrepresents a BIOS color attribute. When converting back touchar, the following happens:- If

fgandbgare BIOS colors, andstyleis cleared, the resultingucharrepresents the same BIOS color attribute contained in theTColorAttr(as in the code above). - Otherwise, the conversion results in a color attribute that stands out, i.e. white on magenta, meaning that the programmer should consider replacing

uchar/ushortwithTColorAttr/TAttrPairif they intend to support the extended color attributes.

The same goes for

TAttrPairandushort, considering that it is composed of twoTColorAttr. - If

A use case of backward-compatibility within Turbo Vision itself is the TPalette class, core of the palette system. In its original design, it used a single data type (uchar) to represent different things: array length, palette indices or color attributes.

The new design simply replaces uchar with TColorAttr. This means there are no changes in the way TPalette is used, yet TPalette is now able to store extended color attributes.

TColorDialog hasn't been remodeled, and thus it can't be used to pick extended color attributes at runtime.

Example: adding extended color support to legacy code

The following pattern of code is common across draw methods of views:

void TMyView::draw()

{

ushort cFrame, cTitle;

if (state & sfDragging)

{

cFrame = 0x0505;

cTitle = 0x0005;

}

else

{

cFrame = 0x0503;

cTitle = 0x0004;

}

cFrame = getColor(cFrame);

cTitle = getColor(cTitle);

/* ... */

}In this case, ushort is used both as a pair of palette indices and as a pair of color attributes. getColor now returns a TAttrPair, so even though this compiles out-of-the-box, extended attributes will be lost in the implicit conversion to ushort.

The code above still works just like it did originally. It's only non-BIOS color attributes that don't produce the expected result. Because of the compatibility between TAttrPair and ushort, the following is enough to enable support for extended color attributes:

- ushort cFrame, cTitle;

+ TAttrPair cFrame, cTitle;Nothing prevents you from using different variables for palette indices and color attributes, which is what should actually be done. The point of backward-compatibility is the ability to support new features without changing the program's logic, that is to say, minimizing the risk of increasing code complexity or introducing bugs.