DNA barcode browser

Interactive web app to explore DNA barcode data sourced from DwCA files.

App: https://dna-barcode-browser.herokuapp.com

Screencast: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jjXuWfofMPg

Manuscript: Short note on the app is in the folder manuscript. This was submitted to bioRxiv and rejected(!). Uploaded instead to Zenodo doi:10.5281/zenodo.4266482

Background

The goal of this app is to suggest a possible interface for exploring DNA barcode data in GBIF. As this data becomes more common it raises the issue of how best to display and explore it. Classical occurrence data (a taxonomic name, a locality, a date) can be readily displayed as lists of occurrences, or as dots on a map. Barcode data comes with a DNA sequence that is potentially rich in information that is not made use of in lists or maps. Phylogenetic trees are an obvious visualisation, but computing these can be computationally demanding. For example, given a set of DNA sequences, typically we would construct a multiple sequence alignment, then compute a tree using a sophisticated statistical model of sequence evolution. Searching for similar sequences is also computationally challenging, the default approach is to use existing software such as BLAST to index sequences.

This project attempts to tackle these problems using Elasticsearch, a search technology already used by GBIF. By treating DNA sequences as text strings and using Elasticsearch’s built in n-gram tokeniser, we can find similar sequences using a full text search (in effect we are “Googling” DNA sequences, cf. Hajibabaei and Singer). N-grams are substrings of characters, where n is the number of characters in the substring.

In the context of biological sequences they are also known as “k-mers”, where k is the length of a subsequence. There are techniques for computing pairwise distances between DNA sequences based on k-mers, which means we can avoid the costly sequence alignment step. Instead of comparing the entire sequence we generate all possible k-mers and count their frequencies. For k=5 there are 45 = 1024 possible k-mers for sequences comprising the bases [A, C, G, T]. Yang and Zhang have shown that k=5 gives reasonable results for phylogenetic inference, so this was chosen for both the phylogeny construction and the n-gram indexing.

These two steps (n-gram indexing and k-mer phylogeny construction) enable us to interactively explore DNA barcode data.

Other work

There are already some striking visualisations of phylogenies and geography, such as Microreact (Argimón et al.) and Nextstrain (Hadfield et al.). These tools compute all the results needed for a visualisation (e.g., phylogenetic tree) offline, then generate a web app to display the results. In contrast, the trees in the DNA barcode browser are created “on the fly” depending on the sequences the user has selected (either by searching by sequence or geography).

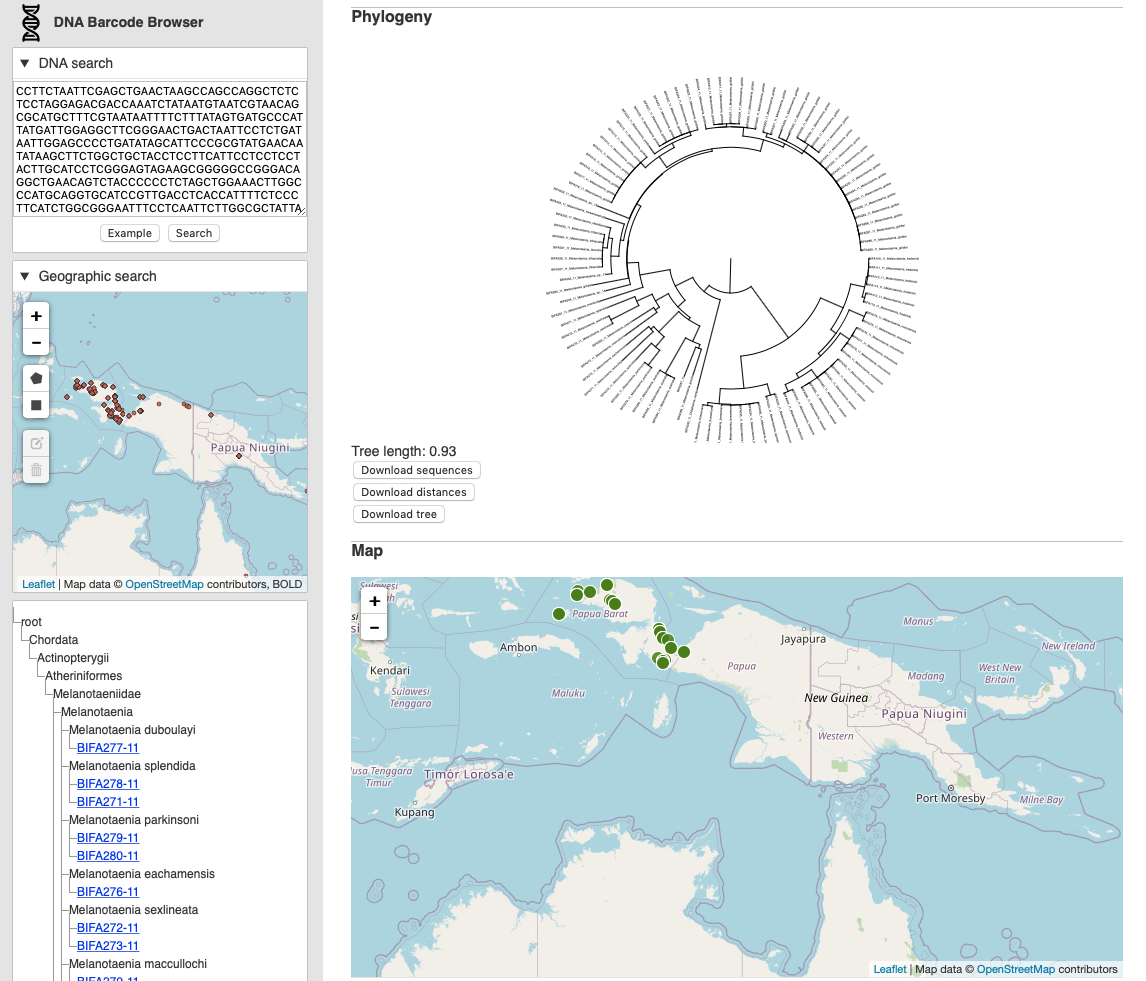

Using the app

There are two ways to use the app. The first is modelled on [BLAST](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BLAST_(biotechnology). In the “DNA search” box you paste in a DNA sequence and press “Search”. The app searches the database for similar sequences, if it finds any it returns them and then computes a phylogenetic tree for those sequences. The sequences are also plotted on a map, and displayed as a list.

The second method is to search spatially. Using the “Geographic Search” map you can draw a polygon on the map that corresponds to the area within which you want to search. The database retrieves sequences in that area, and as before, computes a tree, shows the sequences on a map, and displays a list.

The tree and map are interactive, you can pan and zoom the tree and the map. The total branch length of the phylogeny (in units of pairwise k-mer distance) is displayed as a crude measure of phylodiversity (Faith, 1992) to help give a sense of how much genetic diversity the tree represents. You can also download the (unaligned) DNA barcodes in FASTA format, get the pairwise distances in NEXUS format suitable for input into programs such as PAUP* and Splitstree, and download the tree in Newick format.

Limitations and future directions

The interface could be refined and the displays of tree, map, and list linked together using “brushing” (that is, selecting a node in a tree could also highlight the corresponding location in the map and in the list). There are other visualisations that could be used, such as Klee-plots (Stoeckle & Coffran), histograms of pairwise sequence distance, and plotting the phylogeny on the map (see Page, 2015).

The primary goal of this tool is one of data exploration, so that the user gets a sense of what barcode data is available, and the insights we can get from phylogenetic trees of that data. For example, a cursory glance at a tree can tell us whether we have densely sampled closely related lineages, or sparsely sampled divergent linages.

For this to be the basis of more analytical approaches, we would need to introduce measures of phylogenetic diversity and sample geographically comparable areas. For example, we could divide the globe into comparable size areas using a discrete grid and use the k-mer approach to build phylogenies for samples of sequences taken from each cell in that grid.

Under the hood

Data in the form of Darwin Core Archives (DwCA) is converted into JSON documents for uploading to Elasticsearch. The DwCA could come from GBIF downloads, but for this demo the data comes from BOLD. I have written scripts to retrieve data from BOLD and convert to DwCA format.

The sequences are indexed as n-grams where n is 5 using the following index structure:

{

"mappings": {

"properties": {

"geometry.coordinates": {

"type": "geo_point"

},

"consensusSequence": {

"type": "text",

"analyzer": "my_ngram_analyzer"

},

"dynamicProperties" : {

"type": "object",

"enabled": false

}

}

},

"settings": {

"analysis": {

"analyzer": {

"my_ngram_analyzer": {

"tokenizer": "my_ngram_tokenizer"

}

},

"tokenizer": {

"my_ngram_tokenizer": {

"type": "nGram",

"min_gram": "5",

"max_gram": "5",

"token_chars": ["letter", "digit"]

}

}

}

}

}Note that the DNA barcodes in the consensusSequence field are indexed as n-grams. We also suppress indexing of the dynamicProperties field as this results in too many unique elements for Elasticsearch to index.

To visualise the sequences we compute a phylogenetic tree. This needs to be done “on the fly” so speed is vital. Pairwise distances between the sequences are computed using k-mers, these distances are then used compute a neighbour-joining tree using Simonsen et al. “Rapid Neighbour-Joining” algorithm using code biosustain/neighbor-joining. .

Elasticsearch

Local server for development and debugging set up using Kitematic.

Remote set up on Bitnami. Note that following Bitnami’s instructions we need to do this:

network.host: Specify the hostname or IP address where the server will be accessible. Set it to 0.0.0.0 to listen on every interface.Then we make sure to open the port using the Google Console. For direct connection to Elasricsearch (not recommend) open 9200, for connection via Apache with basic authentication open port 80 (note that this means you will need to add ELASTIC_USERNAME and ELASTIC_PASSWORD to the Heroku Config Vars.

Securing Elasticsearch

After releasing this app the Elasticsearch index regularly seemed to disappear, to be replaced with spurious indices. Eventually I discovered that this was a meow attack as the Elasticsearch instance not password protected by default by Bitnami, see https://github.com/rdmpage/dna-barcode-browser/issues/6.

To fix this I followed Bitnami’s instructions Add Basic Authentication And TLS Using Apache, with some slight tweaks.

- To install the Apache web server execute the following commands:

sudo apt-get install apache2

- Create a new VirtualHost file

sudo nano /etc/apache2/sites-available/elasticsearch-http-vhost.conf

- Add the following content (note that user is called “user”)

<VirtualHost 127.0.0.1:80 _default_:80>

ServerAlias *

ProxyPass / http://127.0.0.1:9200/

ProxyPassReverse / http://127.0.0.1:9200/

AllowEncodedSlashes On

<Location />

AuthType Basic

AuthName "Introduce your ElasticSearch creadentials."

AuthBasicProvider file

AuthUserFile /opt/bitnami/passwd

Require user user

</Location>

</VirtualHost>- Execute the following command to generate the Apache passwords file:

sudo htpasswd -c /opt/bitnami/passwd user

-

When prompted for a password, use the one displayed by Bitnami on the web page for the virtual machine.

-

Enable the new created virtual host:

sudo ln -s /etc/apache2/sites-available/elasticsearch-http-vhost.conf /etc/apache2/sites-enabled/

- Enable the mod_proxy and mod_proxy_http modules:

sudo a2enmod proxy_http

- Restart the Apache server:

sudo systemctl restart apache2

If everything works then curl -L 127.0.0.1 will return a HTTP 401 error, but curl -L http://user:password@127.0.0.1/ will return something like:

{

"name" : "bitnami-elasticsearch-5754",

"cluster_name" : "bnCluster",

"cluster_uuid" : "SpESnodpSTeCk4zkziRljQ",

"version" : {

"number" : "7.9.1",

"build_flavor" : "oss",

"build_type" : "tar",

"build_hash" : "083627f112ba94dffc1232e8b42b73492789ef91",

"build_date" : "2020-09-01T21:22:21.964974Z",

"build_snapshot" : false,

"lucene_version" : "8.6.2",

"minimum_wire_compatibility_version" : "6.8.0",

"minimum_index_compatibility_version" : "6.0.0-beta1"

},

"tagline" : "You Know, for Search"

}Pipeline for uploading data

BOLD to DWCA

Given a BOLD identifier (or other query) use bold2dwca.php to fetch data and convert to a DWCA file. We do this so that we can provide a way to upload BOLD to GBIF, as well as mimic process whereby someone downloads DWCA with barcodes from GBIF.

DWCA to SQL index

DWCA splits the data into several different files based on data type (e.g., occurrences, sequences, images), but we want to assemble those into a single JSON document for indexing in Elastic. We could do this by creating a document for each occurrence and then updating that document with sequence and image information, but that means we can’t make use of Elastic’s bulk upload feature. Hence, we use dwca_to_sql.php to store the data (one row per data type).

CREATE TABLE `dwca` (

`id` varchar(32) NOT NULL DEFAULT '',

`type` varchar(32) NOT NULL,

`data` text,

PRIMARY KEY (`id`,`type`)

) ENGINE=InnoDB DEFAULT CHARSET=utf8;We then create a view that lists the unique identifiers:

CREATE ALGORITHM=UNDEFINED DEFINER=`root`@`localhost` SQL SECURITY DEFINER VIEW `ids`

AS SELECT

distinct `dwca`.`id` AS `id`

FROM `dwca`;Upload to Elastic

To upload the data we take the list of unique identifiers, assemble the corresponding data into a single JSON document, then send that to Elastic. These operations are done by to_elastic.php.

Elastic indices

Early on I had errors such as :

{"error":{"root_cause":[{"type":"illegal_argument_exception","reason":"Limit of total fields [1000] in index [dna] has been exceeded"}],"type":"illegal_argument_exception","reason":"Limit of total fields [1000] in index [dna] has been exceeded"},"status":400}A work around was

{

"index.mapping.total_fields.limit": 10000

}However once I stopped indexing dynamicProperties this was no longer a problem.

References

Argimón S, Abudahab K, Goater R, Fedosejev A, Bhai J, Glasner C, Feil E, Holden M, Yeats C, Grundmann H, Spratt B, Aanensen D. 30/11/2016. M Gen 2(11): doi:10.1099/mgen.0.000093

Edgar RC. 2004. Local homology recognition and distance measures in linear time using compressed amino acid alphabets. Nucleic Acids Research 32:380–385. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkh180.

Faith DP. 1992. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biological Conservation 61:1–10. DOI: 10.1016/0006-3207(92)91201-3.

Hadfield, J., Megill, C., Bell, S. M., Huddleston, J., Potter, B., Callender, C., … Neher, R. A. (2018). Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics, 34(23), 4121–4123. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty407

Hajibabaei M, Singer GA. 2009. Googling DNA sequences on the World Wide Web. BMC Bioinformatics 10:S4. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-S14-S4.

Kuksa, P., & Pavlovic, V. (2009). Efficient alignment-free DNA barcode analytics. BMC Bioinformatics, 10(S14). doi:10.1186/1471-2105-10-s14-s9

Page R. 2015. Visualising Geophylogenies in Web Maps Using GeoJSON. PLOS Currents Tree of Life. DOI: 10.1371/currents.tol.8f3c6526c49b136b98ec28e00b570a1e.

Shaun Wilkinson. 2018. shaunpwilkinson/kmer: kmer v1.0.2. Zenodo. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1227690.

Simonsen, M., Mailund, T., & Pedersen, C. N. S. (n.d.). Rapid Neighbour-Joining. Algorithms in Bioinformatics, 113–122. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-87361-7_10

Stoeckle MY, Coffran C. 2013. TreeParser-Aided Klee Diagrams Display Taxonomic Clusters in DNA Barcode and Nuclear Gene Datasets. Scientific Reports 3:1–6. DOI: 10.1038/srep02635

Yang, K., & Zhang, L. (2008, January 10). Performance comparison between k-tuple distance and four model-based distances in phylogenetic tree reconstruction. Nucleic Acids Research. Oxford University Press (OUP). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkn075

Acknowledgements

- Code for neighbour-joining tree comes from biosustain/neighbor-joining.

- Tree display code is from treelib-js

- SVG zoom uses jquery-svg-pan-zoom or ariutta/svg-pan-zoom

- Maps displayed using Leaflet.js.

- Data from BOLD