MSON

MSON

The MSON compiler allows you to generate apps from JSON. The ultimate goal of MSON is to allow anyone to develop software visually, but you can also use pieces of MSON to turbo charge your development:

-

MSON is a subset of JSON and comprised of just a few building blocks, yet it is as powerful as its non-declarative counterparts. MSON supports validation, inheritance, composition, pub/sub, access control, templating and various other features.

-

MSON is particularly useful in software that generates other software, e.g. a form builder. This is because MSON is just JSON, so it is easy to consume, modify and store.

-

MSON is framework agnostic, but the default mson-react rendering layer uses React and Material-UI to generate a UI. The rendering layer is pluggable and can be written to support any framework and UI library.

-

The MSON library can also be used without any UI dependecies, which makes it great for things like data validation in both the front and back ends.

You can read more about why I created MSON at Creating a New Programming Language That Will Allow Anyone to Make Software.

Live Demo

Getting Started

Demo Apps on Codesandbox

Check out the To Do List and Basic App, which will let you play with MSON in real-time.

Getting Started App

The best way to get started with MSON is to play with the Getting Started App. In just a few lines of MSON, you'll generate an app that can list, edit, filter and sort a list of contacts. And, for extra fun, you can use Firebase to make it real-time capable.

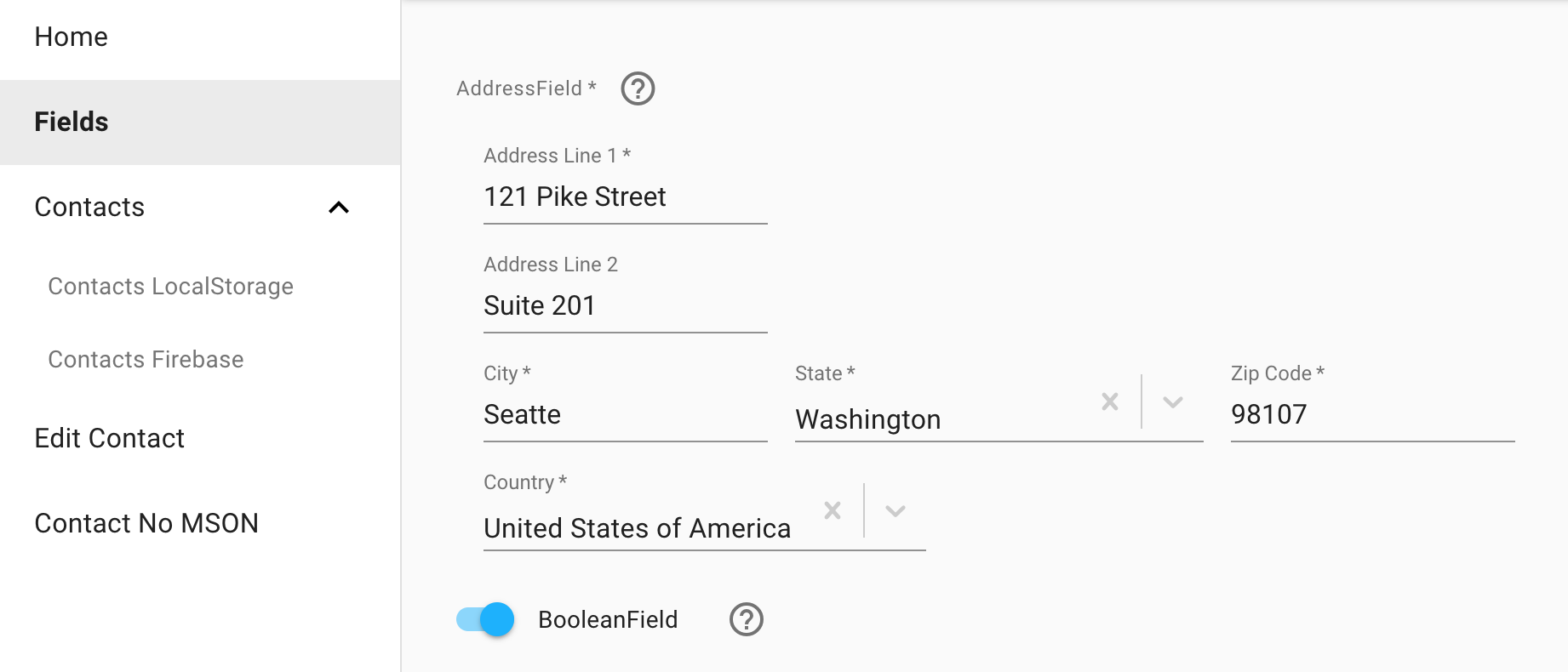

Autogenerate forms in React and Material-UI with MSON

Implementing great forms can be a real time-waster. With just a few lines of JSON, you can use MSON to generate forms that perform real-time validation and have a consistent layout.

MSON Demo

After you have played with the Getting Started App you may find it useful to fire up the MSON demo:

- $

git clone https://github.com/redgeoff/mson-react && cd mson-react && yarn install - $

yarn start - Visit http://localhost:3000 in a web browser

The MSON code can be found in components. Here are some highlights:

Language Principles

Declarative Syntax

MSON is short for Model Script Object Notation, which is intentionally similar to JSON (JavaScript Object Notation). In fact, MSON is a subset of JSON, so if you know JSON then you know the syntax of MSON!

Declarative languages are much easier for software to read and write as they define what the software must do without stating exactly how to do it. And JSON is a great foundation on which to build. It contains just a few main constructs, is ubiquitous and supported by a vast ecosystem.

Components

The smallest building block in MSON is called a component. Components maintain state and can also control presentation and are very similar to the components now commonplace in most web frameworks. Components can inherit, contain or wrap other components. The rendering layer supports plugins for different environments and the default plugin supports React and Material-UI. Use of the rendering layer is optional, so components can be used on both the front end and back end.

A simple form component used to collect a name and email address could look like:

{

name: 'MyForm',

component: 'Form',

fields: [

{

name: 'name',

component: 'TextField',

label: 'Name',

required: true

},

{

name: 'email',

component: 'EmailField',

label: 'Email'

},

{

name: 'submit',

component: 'ButtonField',

label: 'Submit',

icon: 'CheckCircle'

}

]

}The majority of the remaining examples in this post will focus on form components, as they are simple to visualize, but MSON can support any type of component, e.g. menus, snackbars, redirects, etc… In addition, you can use JavaScript to create user-defined components that can pretty much do anything else you can imagine.

Validators

Each field has a default set of validators, e.g. the EmailField ensures that email addresses are in a valid format. You can also extend these validators for a particular field or even for an entire form.

For example, you can prevent the user from entering nope@example.com:

{

name: 'MyForm',

component: 'Form',

fields: ...,

validators: [

{

where: {

'fields.email.value': 'nope@example.com'

},

error: {

field: 'email',

error: 'must not be {{fields.email.value}}'

}

}

]

}Template parameters like {{fields.email.value}} can be used to inject the values of fields. And, you can use any MongoDB-style query in the where. For example, if you had password and retypePassword fields, you could ensure that they are equivalent with:

where: {

'retypePassword.fields.value': {

$ne: '{{fields.password.value}}'

}

}Events & Listeners

Changes to properties in a component generate events and you can create listeners that respond to these events with actions. There are basic actions that set, emit, email, contact APIs, etc… and custom actions can also be built using JavaScript.

The following example sets the value of the email field based on the value supplied in the name field when the user clicks the submit button:

{

name: 'MyForm',

component: 'Form',

fields: ...,

validators: ...,

listeners: [

{

event: 'submit',

actions: [

{

component: 'Set',

name: 'fields.email.value',

value: '{{fields.name.value}}@example.com'

}

]

}

]

}We can also make this action conditional, e.g. only set the email if it is blank:

listeners: [

{

event: 'submit',

actions: [

{

component: 'Set',

if: {

'fields.email': {

$or: [

{

value: null

},

{

value: ''

}

]

}

},

name: 'fields.email.value',

value: '{{fields.name.value}}@example.com'

}

]

}

]And sometimes we want to nest actions so that a condition is met before all actions are executed:

listeners: [

{

event: 'submit',

actions: [

{

component: 'Action',

if: {

'fields.email': {

$or: [

{

value: null

},

{

value: ''

}

]

}

},

actions: [

{

component: 'Set',

name: 'fields.email.value',

value: '{{fields.name.value}}@example.com'

},

{

component: 'Set',

name: 'fields.name.value',

value: '{{fields.name.value}} Builder'

}

]

}

]

}

]Template Queries

It is possible to chain together a series of actions to accomplish almost anything. The downside to this approach is that your code can quickly become bloated and you may be required to create a number of custom actions. Consider an example where we want to increment the value of a counter if the counter is not null. Assume that we have a custom component called Increment, which increments values and does not work with null values:

{

name: 'MyForm',

component: 'Component',

schema: {

component: 'Form',

fields: [

{ name: 'counter', component: 'IntegerField' }

{ name: 'submit', component: 'ButtonField' }

]

},

listeners: [

{

event: 'submit',

if: {

'fields.counter.value': null

},

actions: [

{

// The counter is null so assume it is now 1

component: 'Set',

name: 'fields.counter.value',

value: 1

}

],

else: [

{

// Assume Increment doesn't work with null values

component: 'Increment',

value: '{{fields.counter.value}}'

},

{

component: 'Set',

name: 'fields.counter.value',

// Output of the Increment action above is available at {{arguments}}

value: '{{arguments}}'

}

]

}

]

}Instead, with Template Queries, we can use MongoDB-style aggregation operators to accomplish this functionality in fewer lines of code:

{

name: 'MyForm',

component: 'Component',

schema: ...,

listeners: [

{

event: 'submit',

actions: [

{

component: 'Set',

name: 'fields.counter.value',

value: {

$cond: [

{ $eq: ['{{fields.counter.value}}', null] },

1, // Initial increment

{ $add: ['{{fields.counter.value}}', 1] } // Subsequent increment

]

}

}

]

}

]

}Note: MSON just uses the same syntax as MongoDB, but does not require or depend on MongoDB.

You can use Template Queries to execute custom routines with many other useful operators like $add, $multiply, $filter and $map. And, you can make these routines reusable by wrapping them in a custom Action.

Access Control

Unlike most programming languages, access control is a first-class citizen in MSON, so its easy to use without a lot of work. Access can be restricted at the form or field layers for the create, read, update and archive operations. (MSON is designed to encourage data archiving instead of deletion so that data can be restored when it is accidentally archived. You can, of course, permanently delete data when needed).

Each user can have any number of user-defined roles and access is then limited to users with specified roles. There is also a system role of owner that is defined for the owner of the data. Field-layer access is checked first and if it is missing it will cascade to checking the form-layer access. When the access is undefined at the form layer (and not defined at the field-layer), all users have access.

Here is an example configuration:

{

name: 'MyForm',

component: 'Form',

fields: ...,

validators: ...,

listeners: ...,

access: {

form: {

create: ['admin', 'manager'],

read: ['admin', 'employee'],

update: ['admin', 'owner', 'manager'],

archive: ['admin']

},

fields: {

name: {

create: ['admin'],

update: ['owner']

}

}

}

}Among other things, only users with the admin or manager roles can create records. In addition, only owners of a record can modify the name.

Inheritance

Inheritance is used to add additional functionality to a component. For example, we can extend MyForm and add a phone number:

{

name: 'MyFormExtended',

component: 'MyForm',

fields: [

{

name: 'phone',

component: 'PhoneField',

label: 'Phone Number',

before: 'submit'

}

]

}We can define new validators, listeners, access, etc… at this new layer. For example, we can pre-populate some data, lay out all fields on the same line and disable the email field by creating a listener for the create event:

{

name: 'MyFormExtended',

component: 'MyForm',

fields: ...,

listeners: [

{

event: 'create',

actions: [

{

component: 'Set',

name: 'value',

value: {

name: 'Bob Builder',

email: 'bob@example.com',

phone: '(206)-123-4567'

}

},

{

component: 'Set',

name: 'fields.name.block',

value: false

},

{

component: 'Set',

name: 'fields.email.block',

value: false

},

{

component: 'Set',

name: 'fields.email.disabled',

value: true

}

]

}

]

}Template Parameters

Template parameters are helpful when creating reusable components as they allow you to make pieces of your component dynamic. For example, let’s say that we want our first field and the label of our second field to be dynamic:

{

name: 'MyTemplatedForm',

component: 'Form',

fields: [

'{{firstField}}',

{

name: 'secondField',

label: '{{secondFieldLabel}}',

component: 'EmailField'

}

]

}we can then extend MyTemplatedForm and fill in the pieces:

{

name: 'MyFilledTemplatedForm',

component: 'MyTemplatedForm',

firstField: {

name: 'firstName',

component: 'TextField',

label: 'First Name'

},

secondFieldLabel: 'Email Address'

}Composition

The componentToWrap property allows you to wrap components, enabling your reusable components to transform any component. For example, we can use composition to create a reusable component that adds a phone number:

{

name: 'AddPhone',

component: 'Form',

componentToWrap: '{{baseForm}}',

fields: [

{

name: 'phone',

component: 'PhoneField',

label: 'Phone Number',

before: 'submit'

}

]

}and then pass in a component to be wrapped:

{

name: 'MyFormWithPhone',

component: 'AddPhone',

baseForm: {

component: 'MyForm'

}

}You can even extend wrapped components, paving the way for a rich ecosystem of aggregate components comprised of other components.

Aggregate Components

MSON ships with a number of aggregate components such as the RecordEditor and RecordList, which make it easy to turn your form components into editable UIs with just a few lines of code.

Let’s define a user component:

{

name: 'MyAccount',

component: 'Form',

fields: [

{

name: 'firstName',

component: 'TextField',

label: 'First Name'

},

{

name: 'lastName',

component: 'TextField',

label: 'Last Name'

},

{

name: 'email',

component: 'EmailField',

label: 'Email'

}

]

}we can then use a RecordEditor to allow the user to edit her/his account:

{

name: 'MyAccountEditor',

component: 'RecordEditor',

baseForm: {

component: 'MyAccount'

},

label: 'Account'

}You can also use the RecordList to display an editable list of these accounts:

{

name: 'MyAccountsList',

component: 'RecordList',

label: 'Accounts',

baseFormFactory: {

component: 'Factory',

product: {

component: 'MyAccount'

}

}

}Schemas and Self Documentation

Schemas must be defined for all components, which means that MSON is strongly typed. For example, a schema that defines boolean and date properties may look like:

{

name: 'MyComponent',

component: 'Component',

schema: {

component: 'Form',

fields: [

{

name: 'hidden',

component: 'BooleanField',

help: 'Whether or not the component is hidden'

},

{

name: 'updatedAt',

component: 'DateTimeField',

required: true,

help: 'When the component was updated'

}

]

}

}Schemas can also contain documentation via help properties, which means that components are self-documenting! In addition, schemas are inherited and can be overwritten to allow for more or even less constraints.

User-Defined JavaScript Components

The MSON compiler is written in JavaScript and can run in both the browser and in Node.js. As such, you can use any custom JS, including external JS libraries, to create your own components.

For example, here is a component that uses Moment.js to set a currentDay property to the current day:

import compiler from 'mson/lib/compiler';

import Component from 'mson/lib/component';

import Form from 'mson/lib/form';

import { TextField } from 'mson/lib/fields';

import moment from 'moment';

class MyComponent extends Component {

// className is needed as JS minification strips the constructor name

className = 'MyComponent';

create(props) {

super.create(props);

this.set({

// Define a currentDay property

schema: new Form({

fields: [

new TextField({

name: 'currentDay'

})

]

}),

// Default currentDay

currentDay: moment().format('dddd')

});

}

}

compiler.registerComponent('MyComponent', MyComponent);And then MyComponent can be used in any MSON code.

You can also do things like define custom asynchronous actions, e.g. one that POSTs form data:

import compiler from 'mson/lib/compiler';

import Action from 'mson/lib/actions/action';

import Form from 'mson/lib/form';

import { TextField } from 'mson/lib/fields';

class MyAction extends Action {

className = 'MyAction';

create(props) {

super.create(props);

this.set({

schema: new Form({

fields: [

new TextField({

name: 'foo'

})

]

})

});

}

async act(props) {

const form = new FormData();

form.append('foo', this.get('foo'));

const account = props.component;

form.append('firstName', account.get('firstName');

form.append('lastName', account.get('lastName');

form.append('email', account.get('email');

return fetch({

'https://api.example.com',

{

method: 'POST',

body: form

}

})

}

}

compiler.registerComponent('MyAction', MyAction);And then you can use this in your MSON code:

{

name: 'MyAccountExtended',

component: 'MyAccount',

listeners: [

{

event: 'submit',

actions: [

{

component: 'MyAction',

foo: 'bar'

}

]

}

]

}Using MSON in Any JavaScript Code

There is always parity between compiled and uncompiled components so that the same feature set is supported by both compiled and uncompiled code. For example, our same MyAccount component can also be defined as:

import Form from 'mson/lib/form';

import { TextField, Email } from 'mson/lib/fields';

class MyAccount extends Form {

// className is needed as JS minification strips the constructor name

className = 'MyAccount';

create(props) {

super.create(props);

this.set({

fields: [

new TextField({

name: 'firstName',

label: 'First Name'

}),

new TextField({

name: 'lastName',

label: 'Last Name'

}),

new EmailField({

name: 'email',

label: 'Email'

})

]

})

}

}In fact, converting MSON code to this type of code is basically what the compiler does. Although, the compiler doesn’t actually transpile MSON to JS, it merely instantiates JS code based on the MSON definitions.

Since all MSON code can be compiled to JS code, you can use MSON components in any JS code. For example, you can set some fields and validate the data:

import compiler from 'mson/lib/compiler';

// Compile the MyAccount component

const CompiledMyAccount = compiler.compile({

component: MyAccount

});

// Instantiate the JS class with a default value

const myAccount = new CompiledMyAccount({

// Default values

value: {

firstName: 'Bob'

}

});

// Set the remaining data

myAccount.set({

lastName: 'Builder',

email: 'invalid-email@'

});

// Make sure the values are valid

myAccount.validate();

if (myAccount.hasErr()) {

console.log(myAccount.getErrs());

}In other words, you can use MSON in your existing JS code to save time writing complex code. By declaring components in MSON, you’ll remove a lot of boilerplate code and reduce the possibility of bugs. You’ll also have code that has a standard structure and is framework agnostic. And this code doesn’t add any unneeded frameworks or back-end dependencies to your codebase.

Component as a Class or Compiled Component

In the above example, we used:

const CompiledMyAccount = compiler.compile({

component: MyAccount

});whereby, MyAccount is actually a class (compiled component). This can be handy as it means that we didn't have to register MyAccount with the compiler and we can import components using the native constructs present in JavaScript. On the other hand, our definition:

{

component: MyAccount

}can no longer be serialized into a JSON string as it references a JavaScript class. JSON serialization could be a requirement if, for example, we want to store our definitions in a database. MSON gives you the freedom to make this decision as you can always use the following instead:

compiler.registerComponent('MyAccount', MyAccount);

const CompiledMyAccount = compiler.compile({

component: 'MyAccount'

});Reusing MSON Code Throughout the Full Stack

MSON components can be shared by both the front end and back end, allowing for key logic to be written once and then reused. For example, the same form validation rules can be enforced in the browser and by your back-end API.

Moreover, actions can be limited to the backEnd or frontEnd, so that the same component can adjust according to the host environment. For example, you may want a contact form to send an email to the user when it is used on the back end, but only display a snackbar on the front end:

{

component: 'Form',

fields: [

{

name: 'email',

component: 'EmailField',

label: 'Email'

},

{

name: 'message',

component: 'TextField',

label: 'Message'

},

{

name: 'Submit',

component: 'ButtonField',

label: 'Submit'

}

],

listeners: [

{

event: 'submit',

actions: [

{

// Send an email on the back end

component: 'Email',

layer: 'backEnd',

from: '{{fields.email.value}}',

to: 'noreply@example.com',

subject: 'My message',

body: '{{fields.message.value}}',

// Detach so that user doesn't have to wait for email

// to send

detach: true

},

{

// Display a message to the user on the front end

component: 'Snackbar',

layer: 'frontEnd',

message: 'Thanks for the message'

}

]

}

]

}In/Out Properties

Sometimes you want the presence of data, but don’t want it to be written or read from the back end. For example, your default user component may not allow for the password to be read or edited:

{

name: 'MyUser',

component: 'Form',

fields: [

{

name: 'name',

component: 'TextField',

label: 'Name'

},

{

name: 'email',

component: 'EmailField',

label: 'Email'

},

{

name: 'password',

component: 'PasswordField',

label: 'Password',

hidden: true,

in: false,

out: false

}

]

}However, your EditPasswordForm may need to allow such access:

{

name: 'EditPasswordForm',

component: 'MyUser',

listeners: [

{

event: 'create',

actions: [

{

// Hide all fields

component: 'Set',

name: 'hidden',

value: true

},

{

// Show password field

component: 'Set',

name: 'fields.password.hidden',

value: false

},

{

// Allow user to write password to the back end

component: 'Set',

name: 'fields.password.out',

value: true

}

]

}

]

}MSON Design

Check out MSON Design for more info on why certain conventions were chosen.