Briefly

- Yes, it can access internal floppy drives on your PC.

- Yes, it can directly work with KryoFlux (starting with 1.6 also for direct writing).

- Yes, it can directly work with Greaseweazle.

- Yes, this Windows XP application is confirmed to work in Linux via Wine (see this FAQ).

Introduction (aka. "Why and What For")

It all started in Spring of 2014 when I, for a reason which I no longer remember, wanted to access 3.5" floppies of an 8-bit ZX Spectrum computer clone (branded Didaktik) on a modern PC. I already knew that this was possible as I saw (and worked with) several PC-designed special utilities to create images of floppies of Atari ST, CP/M, etc. The utilities had poor interfaces (if any) and very limited possibilities on how to manipulate files (they were rather dump tools instead of disk explorers). I knew there existed the OmniFlop tool for… well, I don't know – I never managed to run it due to strange (yet free) licencing and the author not responding to my e-mail requests to get a licence. But as far as I know, it should be another pure dump tool. I knew there existed the SamDisk tool which I worked with until then as it offered soft-grained possibilities on creating images of floppies, including the heavily copy-protected ones!

I liked that idea of OmniFlop bridging floppy formats of dozens of disk operating systems (DOSes), although not really understanding them (recall, its a dumping tool). I also liked the clear usage of SamDisk and its possibility to work with even copy-protected floppies. I liked the specialized tools that could (in more or less cumbersome way) extract the files of "their" floppies by understanding the floppy contents. So I asked myself: Has anyone already combined everything together? If yes, I unfortunately couldn't find such application.

The Real and Imaginary Disk Editor (RIDE)

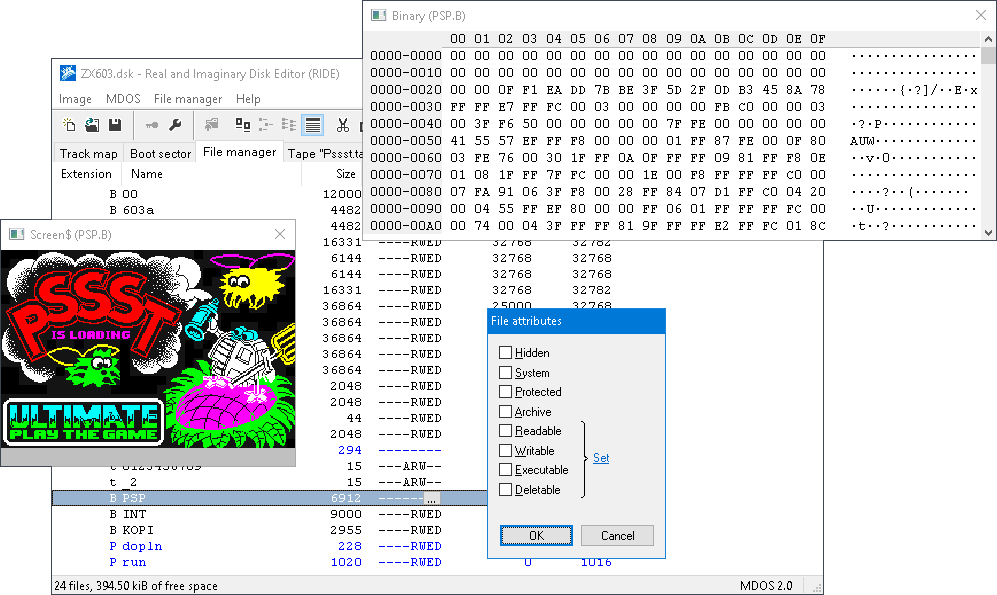

As I was missing something in each application I tried, I created my own one and named it Real and Imaginary Disk Editor (or simply RIDE). It serves for direct access to filesystems of legacy platforms, including the once very popular MS-DOS. The filesystems can be stored both on physical floppies and in images (hence the name "real and imaginary"). RIDE is suitable for both novice and expert users in a given platform. Novice users will find it easy to use for their early experimentations, while expert users will appreciate its advanced features that facilitate direct data modification and recovery. If the DOS you need is not implemented, you at least can access the floppy at the sectors level, or implement it yourself and then ideally commit the result to this repository, so that we all can benefit from your efforts.

Beginning at the Lowest Level

Now on how it functions. The access to your data may begin at the magnetic flux level either through supported devices (like KryoFlux or Greaseweazle V4.x) or through disk images that can represent the fluxes (like KF Streams, SuperCard Pro, or HxC2001). I have implemented several decoding algorithms in RIDE to extract zeros and ones from the magnetic record (note that they are actually not my inventions – adopted from elsewhere and authors credited in algorithm names). Each of the algorithms has a different ratio of speed and robustness, and is thus suitable for different levels of corruption in the data (for instance, a fast algorithm deciphers well a good signal but is more likely to fail when a "surprise" occurs in the signal).

The lowest level can be viewed by right-clicking a track in the Track Map tab, as the following figure shows.

Working with Sector Data

With zeros and ones extracted from magnetic fluxes, the binary must be decoded to discover the structure of a track. RIDE currently supports only the widespread MFM encoding but others are to come. Another way how to come to this point is by opening an image with or without explicit track layout (.hfe, .ipf, .dsk, .ima, .img, .raw, etc.).

The Track Map tab shows the structure of the open disk, possibly with a real timing that is occuring on the disk. By right-clicking a track or a sector, you can navigate to that track or sector to see its content in hexa-mode, rescan a track, or eventually "mine" a track.

"Mining" is a fancy name for an operation to recover corrupted data by brute force. You set the mining target (for instance, that all DOS standard sectors must be healthy, as in the image underneath this paragraph) and a method how to approach the target. There's currently just one method of repetitively reading the erroneous track until the target is eventually met. Simple as it really is, this method allowed me to save data from many disks – I launched the mining and gained both hands free (and all the time) to play with the pressure of drive's heads, their position, and/or floppy disk angle. Until, suddenly, the mining ended and I knew I got the track saved!

Disk Operating Systems

Knowing the structure of tracks, RIDE attempts to recognize sectors. When first opening a disk, each disk operating system (DOS) from a list I call the recognition sequence gets crack on the disk to see "if the sectors look familiar." RIDE then uses the first DOS in the sequence that "finds the disk familiar" to mediate access to stored data. The recognition sequence can of course be adjusted (see FAQ).

The policy of DOS implementations in RIDE (see FAQ) is to not hide anything from the user: boot sector(s), FAT items, directory entries, hidden files, file attributes and other information is all at your disposal.

Writing

Up to this point, I presented mostly reading capabilities. However, the flow of actions can also be reverted and RIDE can become a disk creator. There are virtually two ways how to let it create a disk – either by custom composition or by dumping an existing disk.

Creating a disk with custom content means (1) formatting a disk using one of implemented DOSes (see FAQ), (2) dragging and dropping files/directories into the File Manager tab, (3) expert users will find authoring the remainder of the disk interesting (boot sector, non-standard track layouts, directory tweaks, etc.), and (4) pressing Disk → Save to save all the modifications (see FAQ). RIDE eventually resorts as low as to magnetic fluxes to write each track onto a new disk, standing to its name that be it real or imaginary.

Dumping is the second way of creating a disk. A typical scenario of a collecting archivist like me is to have a real disk as the source and a suitable image disk as the target (see FAQ). However, the combinations of source and target aren't limited and you can dump anything into virtually anything else – naturally, as long as the latter can account for all features of the former. This makes RIDE quite a unique converter between images (see FAQ).

Summary

Here I'd like to pinpoint some highlights that RIDE can offer for your retro-computing archeology:

- It attempts to bridge the gap between classical "import/export tools" and a simple data recovery applications in the realm of free software.

- It can automatically recognize the disk operating system (DOS) and corresponding disk format without user's intervention. Just insert the disk, access it via RIDE and immediatelly work with the files.

- It supports the hard-to-find MDOS 2.0 filing system (originally developed by Didaktik).

- It can read/write/format non-standard MS-DOS track structures, including FAT32 for hard-drive images (Master Boot Record currently not supported, however).

- It doesn't attempt to shield you from any information available in a given filing system – even critical values are at your disposal.

- It allows you to at least dump sectors of unsupported filesystems, including the most common errors (usually part of a copy-protection scheme).

- It supports high-DPI screens.

Compilation and Running (no installation needed, ever!)

RIDE needs Visual Studio 2010 or higher to compile, and Windows XP or higher to run. After cloning the repository, simply click Build → Build Solution while having selected either the Debug or Release configuration, and that's it.

The third Release MFC 4.2 configuration is virtually for my purposes only – I use it to create new public releases here on GitHub. To compile using this configuration, you need to have installed the Windows SDK (that contains all the sources and libraries of the legacy MFC 4.2 platform), plus properly set paths. However, the burden associated with compiling under the Release MFC 4.2 configuration is not worth it when there's the Release configuration, so I won't elaborate the details.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here is just a list of the really frequent ones. The full list can be accessed through Help → FAQ or here on-line.

- What filesystems are supported?

- How do I access a real floppy?

- How do I create an image of a real floppy?

- How do I dump an image back to a floppy?

- How do I format a realy floppy?

- How do I convert one image to another?

Contributing

You can contribute in two ways by either giving me a suggestion on improvement (if you found a bug or want a new feature), or implementing a DOS in which you feel you are an expert (you know the structure of the disk, how files are stored on it, how to eventually tweak the filesystem, how to verify the disk is intact, etc.).